Saturday, January 31, 2009

Rehabilitation?

To conclude the month of January, please take a moment to read Christopher Buckley's powerful piece on Auschwitz-Birkenau here. Certainly the Nazi atrocities have been documented ad nauseum to the point where one would think that in this day and age, the historical factuality of the Holocaust would be considered an incontrovertible truth by men and women of rational mind. But we can never stop being vigilant, lest a bit of "Holocaust fatigue" starts to creep into our collective consciousness. As the video above of the Bishop Richard Williamson painfully illustrates, "never again" is an empty phrase without constant re-affirmation and a perpetual struggle to remind new generations of the horrors of the past.

Andrew Bynum Cheats

You don't normally expect to end up with a level 1 trauma injury at an NBA basketball game. Maybe NHL hockey, but not the NBA. Gerald Wallace got crushed by Lakers center Andrew Bynum the other night (see above), resulting in multiple rib fractures and a "collapsed lung" (in the verbiage of national sports reports.) I hate that phrase. Yes, the lung does sort of "collapse" but it sounds so unheroic and weak-willed, as if the lung simply gave up its ghost from sheer exhaustion. Consider the actual medical term: Pneumothorax. Now isn't that a lot cooler? Sounds like the name of the main protagonist in some sci-fi action film. Pneumothorax. Much better.

A pneumothorax results when the thin membranes lining the alveoli (air sacs of the lung) are ruptured, thereby allowing an abnormal communication between the air we inspire and the thoracic cavity. The cavity fills up with air and compresses the thin, fragile lung tissue in such a fashion (i.e. collapsing the lung) that oxygen exchange is compromised. Furthermore, blood return to the heart is impeded because of the increased intra-thoracic pressure. On exam, a patient suffering from a tension pneumothorax will present with hypotension, hypoxemia, absent breath sounds, hyperresonance to percussion, and distended neck veins. People can die from this without immediate intervention.

The treatment involves decompressing that thoracic cavity. If the patient is in extremis, the best and fastest thing is to place a large bore angiocatheter between the 2nd and 3rd ribs into the pleural cavity. Defintive therapy requires placement of a chest tube into the thoracic cavity. This allows for continuous evacuation of the air that wants to accumulate, lets the lung re-expand, and allows for the thin pleural membranes to heal (usually takes 24-72 hours or so). Gerald Wallace's lung was punctured by the sharp fragments of bone from his rib fractures. Apparently, he's now home and doing well. But don't expect him back on the court for 2-3 months....

Wednesday, January 28, 2009

Bail-out?

I found this amusing (from this month's General Surgery News).

CNN Headline News:

David Cossman, MD, a little-known vascular surgeon from Los Angeles, testified before Congress today, pleading his case for a federal bailout of private-practice physicians who were shuttering their practices in record numbers due to decreasing payment for services and increasing career dissatisfaction over burdensome regulatory interference. Members of the bipartisan Congressional panel appeared annoyed that Dr. Cossman was seven minutes late for his scheduled appearance. He explained that unlike the CEOs of the Big Three automakers who had appealed for money immediately before him, he did not have the use of a corporate G-5 jet to get him to Washington in a timely manner and that he had to rely on Greyhound, which was on schedule until an unexpected early winter storm in Utah had delayed him.

Congressman Barney Frank (D-Mass.) was not sympathetic to Dr. Cossman’s cause and wanted to know why federal money should be used to bail out private practice doctors who had clearly demonstrated their willingness to continue to work hard for little money. Rep. Frank added that federal funds were intended for industries where workers did not work hard and produced inferior products and were therefore facing insolvency, like the Big Three. Henry Paulson, the secretary of the Treasury and an ex officio member of the panel, expressed sympathy but cited lack of economic evidence that the demise of the private practice of medicine in the United States would have any measurable effect on the LIBOR [London Interbank Offered Rate], and that the housing market, already moribund, would not be affected in any material way because older physicians had paid off their mortgages and younger doctors had no reasonable chance of ever owning a home anyway.

Dr. Cossman told the committee members that they misunderstood his testimony and that unlike everyone else, the doctors weren’t asking for money—they just didn’t want any more of it taken away. Sen. Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.) took the microphone, but no one heard what he said because they all had their hands over their ears to protect them from acoustical abrasion. A deaf lip reader told a reporter that Mr. Schumer said no doctor should make more than $80K per year and that health care in the United States had deteriorated to the point that doctors had become a threat to public safety.

Most observers agreed that Dr. Cossman made a strategic blunder by trying to pretend that physicians, generally regarded to be among the highest-paid professionals in the United States, were different in any substantial way from the titans of Wall Street. He told the lawmakers that physicians were not overpaid and that if the government bailed out AIG for $150 billion, they should make its top executives repay the $300 million in golden parachutes before the company got a dime. “At $1,000 a pop, $300 million was enough to pay for every carotid endarterectomy performed in the United States for the next three years.” That seemed to touch a nerve in the perpetually irritated Congressman from New York, Charles Rangel, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee who, pointing to a scar on his neck, jumped to his feet screaming, “I had that operation last year and it didn’t cost me a penny,” at which point an aide whispered in his ear that he had actually had his parotid gland removed and he had just been sent to collection.”

Tuesday, January 27, 2009

The New Standard

I have strong feelings on the laparoscopic appendectomy. So strong that if I were an associate professor of surgery at the University of Bigshot I would be trying to crank out a paper every few months in support of it's beauty and efficacy. In any event (I know, I know, I ought to write up my experiences anyway) I have a series of over 150 patients with acute appendicitis who have been treated by moi with laparoscopic exploration, appendectomy, and sometimes peritoneal lavage (depending on severity of contamination). This series includes all comers; simple early appendicitis, advanced appendicitis, and even cases of purulent peritonitis. The end reslt: 0% infection rate. No superficial wound infections, no intra-abdominal abscesses, nada, zilch, nothing. (You see, in a paper for Annals of Surgery you can't write something like 'nada, zilch, nothing' without prevailing editorial compunction like you can in a blog {I know, lousy excuse}) I think that's pretty good. Zero percent. Maybe I'm getting ahead of myself, maybe my next ten appies will have infectious complications, thereby evening everything out knock on wood, but I think maybe I'm on to something. And then I had this case from a few weeks ago that affirmed my faith in the Justice and Truth of Glorious Laparoscopic Appendectomy.

The patient was a 14 year old girl who had been ill for 5 days. In the ER they diagnosed "gastroenteritis" based on a normal WBC count and diffuse pain and admitted her to the floor. The alert pediatrician noticed that the girl's differential showed over 70 bands (I've never seen such a left shift). So she ordered a CT scan that ultimately demonstrated advanced appendicitis and ascites with multiple fluid collections. When I saw the patient she looked like hell. She was 14 years old and she looked on the verge of something awful. Her kidney's were starting to fail and she was having a hard time keeping her blood pressure up. We started antibiotics and rushed her to the OR. We being me. The appendix was obviously perforated and gangrenous and it came out in a matter of minutes. But the damage had already been done. As I rotated the laparoscope around the abdominal cavity I saw pools of pus everywhere. Inflammatory adhesions from the bowels to the abdominal wall spanned the insufflated gap like Spider webs in an old barn. (The pop cultural influence and irresitibility of Spider Man contributed to the unfortunate reflex capitalization in the preceding sentence). So I asked the circulating nurse to get several of the 3 liter saline bags used in urological cases. I was methodical. I started in the right upper quadrant. I aspirated all the gross pus and then proceeded to irrigate/aspirate, irrigate/aspirate, irrigate/aspirate in a soporofic manner (it was after 2 am) until I was satisfied. Then I moved to the right lower quadrant. Then left lower quad. Then up along the left paracolic gutter and splenic flexure. I irrigated like I was watering a lawn in the Arizona summer. My assistant had brought his Ipod and we listened to everything Meatloaf has ever recorded (not my choice but I usually defer music selections to staff for after hours cases). The case took a little over an hour. I left a Jackson-Pratt drain and sent her to the ICU. The pediatrician called me the next day and asked about possible transfer to a tertiary referral center. Not yet, I said. I had this one. Every day her bands decreased. Her CRP (c-reactive proten, an indicator of overall body inflammation) gradually came down. One day on rounds I walked in and she was putting on make-up and her boyfriend was holding her hand. We need to start thinking about getting you out of here, I said. Her mom concurred. The boyfriend blushed and looked at his cuticles and slowly, but not unnoticeably, withdrew his hand from my patient's.

She went home. She went back to school. It was what we like to call in the professional parlance, a "good outcome". But hell, that's what I expected. That's the way lap appies are supposed to go. After all, I've done over 150 of them already (yeah yeah, I know I said the already.) I reviewed the literature (yeah, we do that in the hinterlands of non-academic medicine) and the data on laparoscopic appendectomy is a litle surprising. You can go to Pubmed and review it yourself but here's the bottom line: laparoscopy is at least as good as open appendectomy although the incidence of intra-abdominal abscess is clearly higher. The italics are utilized for authorial disbelievability. It simply can't be true. Seriously. An open appendectomy implies a limited incision in the right lower quadrant. The visualization is limited. You have no idea what is going on in by the spleen. Sometimes you can shove the sucker down into the pelvis but it's all blind maybe you break into a pus pocket maybe you dont. Maybe you miss a peri-colonic abscess. Laparoscopically I control that point of view. I see that appendix. I see that splenic flexure. I see the gallbladder. I see directly down into the pelvis. So, assuming I intervene appropriately (i.e. aspirating, irrigating, etc) why would there be a higher abscess rate compared to open appendectomy? It simply doesn't make sense. I can irrigate and aspirate and totally control the post operative appearance of the intra-abdominal cavity. Isn't that better, theoretically, than what the open approach affords? Assuming you do it right?

Listen, I'm just a small town (rust town?) general surgeon. I have no academic credentials that ought to sway a patient to choose one form of treatment versus another. But I do have my personal experience. So if you have appendicitis; get thee to a laparoscopist, why wouldst thou be a breeder of infectiousness?

Sunday, January 25, 2009

The Joy of the Master

One of the must-have textbooks for a young surgical resident is Mastery of Surgery. It's a two volume tome detailing the rationale and methods of surgical technique for pretty much every operation we do. Everything from the old Halsteadian radical mastectomy to the laparoscopic Heller myotomy is in that baby. It's a wonderful book. I still peruse through it the night before big cases. But I always hated the title when I was a younger resident. Mastery of surgery. It sounded so typically pompous and bombastic; what one would expect from staid, formalistic surgical academia. The word "mastery" nagged at me, hinted at something overwrought and unattainable. How could one ever think it would be possible to master all the vagaries and intricacies of general surgery?

But my understanding of what it meant to master a profession was woefully inadequate. It isn't about memorizing the steps to a bunch of operations. What I didn't understand was that it was the vagaries and intricacies themselves that separate a true master from the journeyman. You give an apprentice a nice piece of wood and first class tools and the proper instructions, there's a good chance he'll be able to pound out a decent bookcase for you. It will be sturdy and durable and it won't draw negative attention to itself. But a master carpenter can take a bundle of scrap wood and some shabby blunted tools and he'll create a work of art, a centerpiece that guests ask about when they enter your home. Excellence under adverse conditions. A master surgeon is similar in this regard.

I had the privilege of working with such a master surgeon in Chicago as a resident at Rush University Medical Center. Dr. Alexander Doolas was in the latter stages of his career when I was there but he was still one of the busiest surgeons in the hospital. Dr. Doolas is cut from that old school cloth of pure bad ass, no holds barred, no nonsense, work all night, take no excuses, knows more than everyone and isn't afraid to tell you kind of surgeon that used to rule the roosts at big academic centers. (Surgery has now evolved into its kinder and gentler phase of development with work hour reform and the civilizing influence of more women entering the field.) Dr Doolas is about 5'6" and his physique is cut like one of those Bulgarian power lifters. He's always tanned and well dressed outside the OR with his hair immaculately slicked back like Al Pacino in Scent of a Woman. Merely standing in his presence as an intern was terrifying enough. But then he'd open his mouth and this alpha-male, heavily-Greek accented deep baritone would come growling out and you'd literally start dropping pens and papers and maybe even slightly losing control of your sphincter mechanism if you'd done something wrong or forgot a crucial detail. He scared the hell out of me that first year. He was notorious for calling interns randomly in the middle of the night for updates on his ICU patients. The page would come in from an outside line and you'd sprint down to the unit to review the bedside flowsheet before calling it back. And you couldn't make numbers up because Dr. Doolas would often first call the ICU nurse to get the actual answers and compare it with what you told him. So we all ended up hanging out down in the ICU most call nights until after midnight, just in case the old man wanted an update. His big thing was fluids and electrolytes. The man lived for sodium concentrations and potassium losses in bile and the exact chloride composition of pancreatic secretions and urine outputs and the precise balancing of fluid intake versus fluid losses. After Whipples he put in G-tubes (gastrostomy tube) and decompressive J-tubes (jejunostomy) and feeding J-tubes and an NG and you needed to know how much was coming out of each and what it looked and even what it smelled like. He thought he could smell when there was a pancreatic leak. You'd see him digging around on a post-op belly with his bare hands sniffing the end of the drains to determine his next move. Patients with delayed gastric emptying after a Whipple can often lose a lot of water and sodium via NG and G-tube decompression. He sometimes liked to replace those losses not with saline infusions but with the actual fluid itself. So nurses would have to collect the G-tube and decompressive J-tube outputs, put it in a plastic bowl on ice and then refeed it via the feeding J-tube every shift. It was gross but it made sense. It was perfect actually.

On rounds, it was the Dr. Doolas show. He had this charismatic, disarming, eccentrically charming bedside manner that patients just ate up. They loved him. He projected pure confidence and rightness of action. He could walk into an old man's room who'd had a left colectomy and Dr Doolas would pontificate for twenty minutes on how the Persians invaded Greece unprovoked and how they got their comeuppance, and then maybe at the end, right before abruptly leaving, tell the patient that he needed to start eating more potatoes and the patient would nod enthusuastically, as if the Holy Ghost Himself had paid him a visit. He also liked to speak in metaphors. I remember this high maintenance suburban patient who had had a pancreatic resection and she had a thousand questions for Dr Doolas about what was happening and why he was doing certain things. You could tell he was getting annoyed. He took off his glasses (always a sign of something legendary about to happen), started gnawing on the tip, and he held up his hand and that deep voice rolled out at her like a surging wave, "Listen! When you get on an airplane and you're flying to Milwaukee to see your cousin Angelo, do you get up out of your seat and go knocking on the pilot's door and ask him what that knob is and why that light is flashing and how's come the dashboard is beeping like that? Do you? No. You don't. So you let me fly this plane." Some of his metaphors, however, tended to be seemingly ad libbed and barely coherent. You could ask him why he wanted to restrict a patient to scrambled eggs without the yolks, red beans, and unbuttered toast and you were liable to get an answer along the lines of: "Listen. When you get on the bus and you want to get to Evanston there's always an old lady sitting next to you asking if you know where her recipe book is and meanwhile there might be an elephant at the next stoplight but you don't know you so you have to count backwards from 57 by threes until you get to the second prime number and then it's like when the Inuits crossed the Bering Strait and it all becomes obvious. You got it?" And he'd stare at you like you were the stupidest person on earth, your mouth agape, wide eyed, not knowing what in the hell to say, and he'd finally just shake his head and walk away.

In the OR Dr. Doolas was legendary. He was famous for the two hour Whipple. The 20 minute colectomy. He'd hunch over the table, his giant bald head inches from the pancreas, headlamp illuminating an orb of intimate anatomy, and everything he did, every move was filled with purpose. He didn't move fast, he just didn't waste any action. Every maneuver served the purpose of advancing the operation toward its logical conclusion. There was no dicking around, no hemming and hawing, no tentative picking and pawing at tissues. He knew where he was at all times, where he needed to go, and what was necessary to facillitate that end. He didn't let the residents do much unless you were a chief and then, only if he liked you. But operating with Dr. Doolas was beside the point. It was enough to just watch the man in action. Two cases come to mind.

The first was a lady who had been referred to Dr Doolas from an outside hospital. The poor lady had been suffering from an enterocutaneous fistula for over a year. She'd had multiple operations and she hadn't been eating and she just seemed broken and defeated. Green bile leaked from her fistula near the belly button. Scars criss-crossed her abdomen. She looked gaunt and emaciated. Everyone else had given up on her. Dr. Doolas reviewed her scans and xrays and put her on the OR schedule for the next day. Under anesthesia he made a single incision through the midline scar and it soon became apparent we were dealing with a frozen abdomen. A patient who has had peritonitis and multiple operations can develop so much scar tissue that all tissue planes are obliterated; it's as if someone has poured cement between the loops of bowel. There's no free space. Everything is socked in, frozen in place. Every move you make is fraught with hazard. It's easy in these situations to do more harm than good. It's a situation that most surgeons try to avoid and that's why a lot of them end up ultimately with surgeons like Dr Doolas. After the initial incision, Dr. Doolas asked for a hemostat. For the next 60 minutes that's all he used. I watched him wield that blunt tip of the hemostat like chisel, chipping and scraping and carving his way through the scar and granulation tissue until he had isolated the loop of bowel involved in the fistula and separated it from the abdominal wall. It was like watching Rodin create a masterpiece out of a block of granite. In ninety minutes he completed what would have taken any other surgeon 6-8 hours. The patient went home in 4 days, happier than she had been in over a year.

The other case was a thin guy who had had an esophagectomy with a gastric pull-up a number of years ago at an outside institution. He then developed a stricture at the esophagogastrostomy anastomosis in the neck. A previous revision had re-strictured. Multiple attempts at balloon dilatation had failed. Now the man could not swallow even a glass of water. He was dependent on a feeding jejunostomy tube for nutrition. But he missed eating. He missed being able to cut up a perfectly cooked filet, chewing, savoring the juices, the act of swallowing. He wanted to experience it again. No matter what. Telling him no would have been entirely reasonable. He was living at home, surviving, getting by. There was no emergent rationale for further intervention other than the patient's consuming desire to eat again. Dr. Doolas was his last hope. No one else would take the case.

The day of the operation, Dr. Doolas was in one of his happy moods, razzing everyone, laughing easily, seemingly unperturbed by daunting task at hand. Any redo surgery is tricky and trying to revise an anastomosis in the neck for the second time is especially perilous. The neck is a small, contained space and important nearby structures like the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the carotid sheath are at risk of injury. It's a veritable hornet's nest of danger. But once again I watched Dr. Doolas use just a scalpel and a dissecting clamp to carve through dense scar tissue until, miraculously, the striated meaty fibers of the proximal esophagus appeared. From there, he worked his way down to the old anastomosis. Once eveything was dissected out he looked over at me, eyes glinting, and he tossed his head back and laughed, a deep hearty laugh, a guttural guffaw, a sonorous, soulful, Count Dracula sort of laugh from the depths of his being. His hands were momentarily at rest. The moment lingered. And then he started again. Ten minutes later he'd resected the stricture and created a widely patent new end to end anastomosis. The entire case took about 45 minutes. The patient was eating a hamburger three days later.

A master at work. All I did was run the sucker and tie some knots but I learned more from those two cases than in any operation where an attending allowed me to stumble my way through the maneuvers. Just watching. Seeing things the way Dr. Doolas saw them. The sense of undauntedness that he brought to a case. The confidence. The experience and knowledge. The creativity and vision. But I think there was something else, something you can't teach, maybe the most important thing. And it was all contained in that simple baritone laugh, his head tilted back, eyes slightly closed. It was the laugh of pure joy. For in that one brief moment the true master of surgery realizes a rare perfection, the uniqueness of his talents that have allowed him alone to actualize the healing of a complicated patient. There may not be a happier feeling in the world for those chosen few. Without that innate sense of joy, real unadulterated child-like joy, true mastery is unattainable no matter how many books you read or where you train or how many Whipples you watch.....

Thursday, January 22, 2009

Show me the Money

The WSJ health blog today asks where the money is going to come from to fund the anticipated increased remuneration of primary care physicians during the Obama reign. Here're the options given in the online blog poll:

Guess which option is winning? Well of course it's choice "C". Because you know those unscrupulous specialists who do procedures, i.e. non-cognitive medical interventions that a properly trained chimpanzee or even a bonobo could do, ought to be coughing up chunks of change for the poorly paid underclass of primary care docs. Bringing up the rear in the poll is "money ought not to come out of existing health care spending". In other words, don't even think about supplementing physician payment with any more federal money than they already get, dammit!

Why do we keep accepting the conventional wisdom that this is a zero sum game? We just forked out $700 bill to greedy bankers on Wall Street. It took us 50 nanoseconds to decide it would be a good idea to send $80 bill to AIG. If Obama wants to truly reform health care, he's going to need primary care docs; much more than our economy needs a privately owned company like AIG to survive. That puts physicians in the proverbial driver's seat, right? This emphasis on the pay discrepancy between specialists and primary care is just what the policy wonks in DC want. It's the angle they can use to avoid a federal bail out of the American health care train wreck. Just siphon money from the surgeons and proceduralists!

A) Cut subsidies to Medicare Advantage

B) Pay hospitals less for high-margin services such as radiology

C) Lower Medicare reimbursements for care and procedures by specialists

D) The money shouldn’t come out of existing health-care spending

E) Primary care doesn’t need more money

Guess which option is winning? Well of course it's choice "C". Because you know those unscrupulous specialists who do procedures, i.e. non-cognitive medical interventions that a properly trained chimpanzee or even a bonobo could do, ought to be coughing up chunks of change for the poorly paid underclass of primary care docs. Bringing up the rear in the poll is "money ought not to come out of existing health care spending". In other words, don't even think about supplementing physician payment with any more federal money than they already get, dammit!

Why do we keep accepting the conventional wisdom that this is a zero sum game? We just forked out $700 bill to greedy bankers on Wall Street. It took us 50 nanoseconds to decide it would be a good idea to send $80 bill to AIG. If Obama wants to truly reform health care, he's going to need primary care docs; much more than our economy needs a privately owned company like AIG to survive. That puts physicians in the proverbial driver's seat, right? This emphasis on the pay discrepancy between specialists and primary care is just what the policy wonks in DC want. It's the angle they can use to avoid a federal bail out of the American health care train wreck. Just siphon money from the surgeons and proceduralists!

Med City News

Chris Seper (the Cleveland Plain Dealer journalist who interviewed me last summer for the on-line version of the paper) has a new project. He's the founder of an online medical news service called MedCity News. Here's how Chris describes it:

So check it out.

MedCity News is a news service focusing on business, innovation and influence in health care. We don’t write about consumer health or the research in medical journals. Instead, MedCity News covers health care as the economic engine of major American cities.

Our current focus is Northeast Ohio, followed by the rest of Ohio and sections of the Midwest.

So check it out.

Splenic Cysts

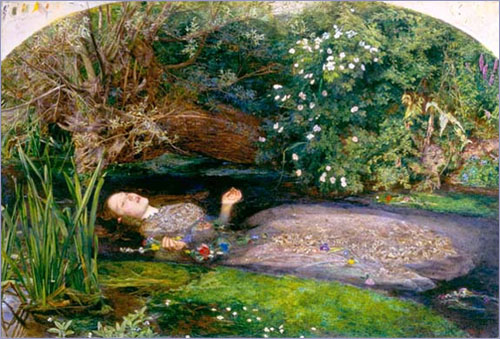

This was a young patient who was sent to me for chronic left upper abdominal pain. She also complained of early satiety and occasional nausea. After about her third or fourth ER visit, a CT scan was obtained which showed a 6x7 cm benign-appearing splenic cyst (pictured above) with some compression of the adjacent stomach.

The cyst did not have the characteristics of a malignancy (septations, calicified wall, etc) and she was symptomatic, so I proposed a laparoscopic partial cystectomy. Splenic preservation is paramount in benign splenic disease, especially in a younger patient. So that's what we did. The surgery went beautifully. Once the cyst was decompressed by needle aspiration (yellow/green fluid) I incised the cyst wall and then divided it circumferentially with the Harmonic scalpel in a relatively bloodless manner. The wall was sent to pathology for a frozen section to rule out malignancy and while we waited I cauterized the aspect of the cyst left in the splenic parenchyma (Argon laser is another option).

Once the path confirmed a benign epidermoid cyst, we took out the ports and closed up shop. Twenty minute case. Fun stuff....

Last one, I promise

One last item on the Gawande paper. And this really happened. I had a patient come in for an elective outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy this week. In the pre-op holding area, right before being wheeled back to the OR suite she informed me that her best friend insisted that she ask "if I followed the checklist that she had read about when doing surgery". Of course, I assured her. I told her about time-outs and sponge counts and how we've been doing it for years. She was suitably impressed. But I think I'll need some sort of assistance remembering an extended checklist like the one Dr Gawande proposes. Perhaps one of those laminated wrist band play book thingies that you see back up and rookie QB's wearing when they have to come into a game. Sterile, of course.......

Saturday, January 17, 2009

Cookbook Redux

I titled my last post a couple days too soon. Check out this link from the WSJ health blog. Dave Snow, CEO of the pharmacy-benefits manager Medco (I have no idea what in the hell that means), has an interesting health care reform proposal. Here, I'll let him describe his little stroke of genius:

Snow said the time has come for doctors to follow set protocols on how to treat patients, and to be paid based on whether they do it. Basically, ‘If X, then do Y,’ and ‘If Y, then do Z,’ sort of stuff.

Yeah, that sort of stuff. Sounds like a surefire solution. It's like algebra. If X (say, congestive heart failure) then one must implement Y (chest xray, diuresis, rule out MI, a million other things, etc). It's simple. And if X is accompanied by Y, Z, W and maybe a little lower case r, then one merely has to integrate the equation with respect to z squared and the solution will present itself. Here's more from Dave Snow (and check out that picture in the link, CEO Snow in all his big white toothed, used car saleman suavity):

“I have no patience for a doctor who says, ‘I’m above it all, I don’t want to practice cookbook medicine,’” Snow says.

Bravo. Because that's exactly what's wrong with American health care. Not enough doctors mindlessly managing their patients according to rigid, universal protocols without regard to individual needs or the subtle variances of the human species. All we needed to do all along was designate a bunch of "smart folks" (like a national Federal Reserve of Health Care!) to get together and hammer out a national health care cookbook for dumb, lowly physicians to follow. My God. It was right there in front of us all along!

Obviously this Chairman Snow character is too contemptible to waste much time on. His idea is vapid and nonsensical and completely detached from any sort of reality that I am familiar with. Let's just hope he doesn't gain any more traction than he already has with Tom Daschle...

Thursday, January 15, 2009

Cookbook Surgery

Atul Gawande has published his "checklist paper" in the latest NEJM. Last year he wrote a profile in the New Yoker on the efforts of Peter Pronovost at Johns Hopkins who had implemented a strict protocol algorithm (or checklist) to be followed for the insertion of central venous catheters, which almost completely eradicated the incidence of catheter-associated infectious complications. So this paper has been eagerly anticipated.

The paper is a prospective collection of 30 day complication data from hospitals around the world for patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Half the patients were subjected to a 19-item Surgical Safety Checklist during the peri-operative period. The checklist includes such items as making sure the correct surgical site is marked, noting allergies, making sure peri-op antibiotics have been given appropriately, and confirming that sponge and instrument counts are correct before closing the incision.

The results are rather astounding. According to the study, death rates were reduced by almost 50% when patients were subjected to this magical checklist. Now that's an amazing achievement. So much so that even Dr. Pronovost is a little suspicious. Surgical teams participating in the study were not blinded to the the study and the patients had not been randomized to either arm. So it's hard to make definitive, standard-of-care conclusions. Closer inspection of the data demonstrates that the biggest improvements were seen in hospitals from third world countries. This makes sense because in the United States, we've already been marking surgical sites and calling pre-op "time-outs" for several years.

Certainly, there is something to be said for meticulous routines when it comes to surgery or other procedures. But do we need mandatory 19 item checklists? Why stop there? Why not make it a 40 item checklist? Why not make the attending surgeon write an essay on how to avoid complications before every case? Or how about having the surgeon and all assistants read the chapter corresponding to the proposed operation from the textbook out loud together (alternating paragraphs) prior to making the incision?

It's good to be organized and precise in surgery. Limited checklists are useful in this regard. We ought to mark our initials on the correct side of the hernia repair. Point taken. Nothing groundbreaking here. We don't want to be operating on the wrong leg or leaving sponges inside bellies. But it's rather a ridiculous leap to think that death rates can be halved just by following a series of irritating instructions on a laminated list.

The paper is a prospective collection of 30 day complication data from hospitals around the world for patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Half the patients were subjected to a 19-item Surgical Safety Checklist during the peri-operative period. The checklist includes such items as making sure the correct surgical site is marked, noting allergies, making sure peri-op antibiotics have been given appropriately, and confirming that sponge and instrument counts are correct before closing the incision.

The results are rather astounding. According to the study, death rates were reduced by almost 50% when patients were subjected to this magical checklist. Now that's an amazing achievement. So much so that even Dr. Pronovost is a little suspicious. Surgical teams participating in the study were not blinded to the the study and the patients had not been randomized to either arm. So it's hard to make definitive, standard-of-care conclusions. Closer inspection of the data demonstrates that the biggest improvements were seen in hospitals from third world countries. This makes sense because in the United States, we've already been marking surgical sites and calling pre-op "time-outs" for several years.

Certainly, there is something to be said for meticulous routines when it comes to surgery or other procedures. But do we need mandatory 19 item checklists? Why stop there? Why not make it a 40 item checklist? Why not make the attending surgeon write an essay on how to avoid complications before every case? Or how about having the surgeon and all assistants read the chapter corresponding to the proposed operation from the textbook out loud together (alternating paragraphs) prior to making the incision?

It's good to be organized and precise in surgery. Limited checklists are useful in this regard. We ought to mark our initials on the correct side of the hernia repair. Point taken. Nothing groundbreaking here. We don't want to be operating on the wrong leg or leaving sponges inside bellies. But it's rather a ridiculous leap to think that death rates can be halved just by following a series of irritating instructions on a laminated list.

Tuesday, January 13, 2009

Traveling Surgeons

Dr. Wes wrote about this today. There's an article in the WSJ about the increasing attractiveness of locum tenens careers for general surgeons. As reimbursements for surgical procedures have dropped off and overhead costs have skyrocketed, it has become more and more difficult to maintain a classical private practice in general surgery, especially in the rural setting. The article outlines the travails of one Dr. Jennifer Peppers who had to shutter her practice and take out a line of credit to pay her mortgage. So now she travels to rural and small town hospitals for one or two-week contracts, knocks out emergency appendectomies and incarcerated hernias and splenectomies, doubles her salary and doesn't have anymore overhead or follow-up hassles. Sounds sweet, right?

Well not so fast. The idea of the "itinerant surgeon" is, rightfully, a career paradigm of last resort. There will always be situations where travelling surgeons will be needed; i.e the small hospitals who need to temporarily fill the void left by retiring or relocating surgeons until a new permanent surgeon is hired. But this is not what you want. You're not a professional if this is what you're doing. You're not practicing general surgery; you've become a technician.

Here's why it's a disastrous model:

1) Continuity of care is tossed out the window. You operate and let someone else take care of your complications two weeks later when you've moved on to the next village. Which is frankly embarassing. In this day and age of resident work hour reform and a creeping shift-worker mentality, the last thing we need is a model that further erodes a surgeon's professional code.

2) You're going to lose your skills. You take emergency call in Podunk, Illinois and maybe you do a few gallbladders and appendectomies but that's about it. Certainly there will be plenty of nights when nothing comes in and you sleep. And you're not going to do any complicated elective cases because you won't be around to take care of the patient afterwards.

3) It's expensive for hospitals. They're paying twice and sometimes four times as much to itinerant surgeons/anesthesiologists as they would to a fulltime community surgeon.

4) It denigrates the professionalism of physicians in general, and surgeons specifically. Physicians are a part of the community in which they serve. The moment that starts to change, the moment a patient realizes that his/her doctor is a contingent entity, beholden to financial incentives, unmoored to the community in which he serves, then we can give up for good all future notions of "doctor as healer" and the idea that physicians pursue a "noble cause".

Here's the deal:

Hospitals (especially smaller community ones) need surgeons. Surgeons need better remuneration and more support from hospitals. There has to be a way to entice surgeons permanently to smaller communities. And not just with the typical three year guaranteed salary deal that we so often see. Perhaps some sort of profit sharing arrangement between hospitals and surgeons is one way. Or longer term salary guarantees. One way or another rural and small town America is going to need the unflashy, bread and butter general surgeon. And this army of fellowship trained colorectal and bariatric and vascular specialists and plastic surgeons graduating from programs isn't going to be there to fill the void. If you want a general surgeon in your community you're going to have to pay for it....

Well not so fast. The idea of the "itinerant surgeon" is, rightfully, a career paradigm of last resort. There will always be situations where travelling surgeons will be needed; i.e the small hospitals who need to temporarily fill the void left by retiring or relocating surgeons until a new permanent surgeon is hired. But this is not what you want. You're not a professional if this is what you're doing. You're not practicing general surgery; you've become a technician.

Here's why it's a disastrous model:

1) Continuity of care is tossed out the window. You operate and let someone else take care of your complications two weeks later when you've moved on to the next village. Which is frankly embarassing. In this day and age of resident work hour reform and a creeping shift-worker mentality, the last thing we need is a model that further erodes a surgeon's professional code.

2) You're going to lose your skills. You take emergency call in Podunk, Illinois and maybe you do a few gallbladders and appendectomies but that's about it. Certainly there will be plenty of nights when nothing comes in and you sleep. And you're not going to do any complicated elective cases because you won't be around to take care of the patient afterwards.

3) It's expensive for hospitals. They're paying twice and sometimes four times as much to itinerant surgeons/anesthesiologists as they would to a fulltime community surgeon.

4) It denigrates the professionalism of physicians in general, and surgeons specifically. Physicians are a part of the community in which they serve. The moment that starts to change, the moment a patient realizes that his/her doctor is a contingent entity, beholden to financial incentives, unmoored to the community in which he serves, then we can give up for good all future notions of "doctor as healer" and the idea that physicians pursue a "noble cause".

Here's the deal:

Hospitals (especially smaller community ones) need surgeons. Surgeons need better remuneration and more support from hospitals. There has to be a way to entice surgeons permanently to smaller communities. And not just with the typical three year guaranteed salary deal that we so often see. Perhaps some sort of profit sharing arrangement between hospitals and surgeons is one way. Or longer term salary guarantees. One way or another rural and small town America is going to need the unflashy, bread and butter general surgeon. And this army of fellowship trained colorectal and bariatric and vascular specialists and plastic surgeons graduating from programs isn't going to be there to fill the void. If you want a general surgeon in your community you're going to have to pay for it....

Thursday, January 8, 2009

Second Opinion

The NY Times explores the issue of whether a community-based doctor has an ethical obligation to inform a patient that the proposed procedure/operation might have a better outcome if performed at a different hospital (i.e. the tertiary referral center in the big city).

This is a big topic in academic circles. It seems every month, an article gets published in one of the big surgical journals advocating that all "complicated" surgical cases get shipped downtown to the giant academic center. Whipple procedures for pancreatic cancer and major liver resections are the classic cases that have been studied with regards to the relationship between surgeon/hospital volume and outcomes. This is not rocket science. The more one performs an operation, the better the results ought to be. If you've done 1000 pancreatic-jejunostomy amastomoses in your career, it's likely that you've picked up a few tricks along the way that will help reduce your complication rates compared to a surgeon who has done 20.

But now, in this era where most general surgeons go on to do fellowships in breast or laparoscopic or colorectal surgery, we are starting to see a clamoring in the surgical literature for pretty much any case other than a hernia or a gallbladder to be sent "downtown". Here's a link to a paper advocating that "breast surgeons" need to be doing all cases for breast cancer. I mean, give me a break. Breast surgery (lumpectomy, mastectomy) is about as technically unchallenging as it gets. But if you can get a paper written and publish it in Annals of Surgery, then maybe you can proclaim yourself "Breast Surgeon Extraordinaire" and never have to take an ER acute abdomen again in your career. (Now I need to write up my lap chole/lap appy experience and publish it this summer in Annals and start a movement demanding that all cases of appendicitis be referred out to the community surgeons. I do more lap appies than the chief of surgery at Memorial Sloan Kettering. Does that he he ought to inform his patient who comes in through the ER that said patient should consider transfer to a smaller hospital in Westchester where a community surgeon {who does far more of these cases} can take care of patient's appendicitis?)

Personally, I would never do a major liver resection in my present situation. I think I could get through a case if forced to do so in an emergency (like a peripheral segmentectomy for a blunt traumatic liver injury), I would not be comfortable doing some sort of anatomic liver resection for a primary tumor or metastasis. I'd want the liver transplant guy downtown doing that case.

I have done three Whipples in the past 14 months. I always offer the option of second opinions and referrals to the tertiary care center downtown. But I don't shy away from the case. I like Whipples. I think I do a pretty good job. I was taught well and I think my surgical principles are sound. If the patient wants me to do it, I will. My outcomes (granted a small sample) are excellent. I don't have anything to apologize for. Same thing with rectal cancers. So I would be uncomfortable telling a patient that he/she will necessarily receive better care and have a superior outcome if he/she opts to have the Big Hospital do the case rather than me. As long as the patient is given options and I continue to honestly assess myself and see how I stack up, I don't see any reason to change the way I practice.

The individual surgeon is the most important factor, I believe. There are hacks at major medical centers who do 5-15 Whipples a year with awful results. Where a surgeon practices is not nearly as important as the skills he/she brings to the table. Obviously, certain ancillary services need to be in place at the local community hospital (good interventional radiology, MRI/CT scanners, a good GI consultant, etc) but ultimately how well you do depends on what happens while you lay asleep on that OR table. Your surgeon's technical expertise and clinical judgment are the paramount factors but the relative merit of them cannot always be deduced based on what the logo is on his/her white coat.

The onus of responsibility inevitably will fall on the surgeon, as it must. Even with internet research and physician ratings and all that garbage, patients want to be able to trust their doctor. If you present yourself as the best option for your patient's disease in that intimate setting of a one on one office visit, the patient is going to want to believe you. That's the essence of the patient/physician relationship. And you're the one who's going to have to live with that. So you better bring the goods.....

This is a big topic in academic circles. It seems every month, an article gets published in one of the big surgical journals advocating that all "complicated" surgical cases get shipped downtown to the giant academic center. Whipple procedures for pancreatic cancer and major liver resections are the classic cases that have been studied with regards to the relationship between surgeon/hospital volume and outcomes. This is not rocket science. The more one performs an operation, the better the results ought to be. If you've done 1000 pancreatic-jejunostomy amastomoses in your career, it's likely that you've picked up a few tricks along the way that will help reduce your complication rates compared to a surgeon who has done 20.

But now, in this era where most general surgeons go on to do fellowships in breast or laparoscopic or colorectal surgery, we are starting to see a clamoring in the surgical literature for pretty much any case other than a hernia or a gallbladder to be sent "downtown". Here's a link to a paper advocating that "breast surgeons" need to be doing all cases for breast cancer. I mean, give me a break. Breast surgery (lumpectomy, mastectomy) is about as technically unchallenging as it gets. But if you can get a paper written and publish it in Annals of Surgery, then maybe you can proclaim yourself "Breast Surgeon Extraordinaire" and never have to take an ER acute abdomen again in your career. (Now I need to write up my lap chole/lap appy experience and publish it this summer in Annals and start a movement demanding that all cases of appendicitis be referred out to the community surgeons. I do more lap appies than the chief of surgery at Memorial Sloan Kettering. Does that he he ought to inform his patient who comes in through the ER that said patient should consider transfer to a smaller hospital in Westchester where a community surgeon {who does far more of these cases} can take care of patient's appendicitis?)

Personally, I would never do a major liver resection in my present situation. I think I could get through a case if forced to do so in an emergency (like a peripheral segmentectomy for a blunt traumatic liver injury), I would not be comfortable doing some sort of anatomic liver resection for a primary tumor or metastasis. I'd want the liver transplant guy downtown doing that case.

I have done three Whipples in the past 14 months. I always offer the option of second opinions and referrals to the tertiary care center downtown. But I don't shy away from the case. I like Whipples. I think I do a pretty good job. I was taught well and I think my surgical principles are sound. If the patient wants me to do it, I will. My outcomes (granted a small sample) are excellent. I don't have anything to apologize for. Same thing with rectal cancers. So I would be uncomfortable telling a patient that he/she will necessarily receive better care and have a superior outcome if he/she opts to have the Big Hospital do the case rather than me. As long as the patient is given options and I continue to honestly assess myself and see how I stack up, I don't see any reason to change the way I practice.

The individual surgeon is the most important factor, I believe. There are hacks at major medical centers who do 5-15 Whipples a year with awful results. Where a surgeon practices is not nearly as important as the skills he/she brings to the table. Obviously, certain ancillary services need to be in place at the local community hospital (good interventional radiology, MRI/CT scanners, a good GI consultant, etc) but ultimately how well you do depends on what happens while you lay asleep on that OR table. Your surgeon's technical expertise and clinical judgment are the paramount factors but the relative merit of them cannot always be deduced based on what the logo is on his/her white coat.

The onus of responsibility inevitably will fall on the surgeon, as it must. Even with internet research and physician ratings and all that garbage, patients want to be able to trust their doctor. If you present yourself as the best option for your patient's disease in that intimate setting of a one on one office visit, the patient is going to want to believe you. That's the essence of the patient/physician relationship. And you're the one who's going to have to live with that. So you better bring the goods.....

Sunday, January 4, 2009

Full Disclosure

Via KevinMD there's a link to a blog by an OB doc named Dr Tuteur. Dr Tuteur discusses a dinner party conversation this past New Year's Eve she had with friends about a doctor's responsibility to inform a patient of an error made in his/her care by a previous doctor. The example they use is: Patient with advanced lung cancer seeing an oncologist. Oncologist notices that a CXR from a few years ago demonstrates the tumor at an early stage. The patient now has has unsalvageable metastatic disease. Question: ought the oncologist inform the patient that an error had been made, that the cancer was missed by the referring primary care physician and the radiologist?

First of all, if it's New Year's Eve and you find yourself at a dinner party where the dominant topic of discussion is medical ethics, it's probably safe to assume that you've made some sort of horrible mistake in choosing your dinner companions and you ought to explore all possible modes of escape from said gathering. I mean, it's New Year's Eve right? Let's drink some champagne and rant about the Browns and tell a few funny stories.

But an issue like this is generally handled in an overly simplified fashion. It's a nice little thought experiment and well reasoned arguments can be made for telling versus not telling but the reality of such situations is usually much more nuanced and complex. To aver that one ought to always inform a patient of a past error is dangerously rigid and dogmatic. Likewise, to maintain that you would never reveal such information to a patient only serves to create the impression that physicians just look out for each other and are not a patient's advocate.

It's not a black and white moral conundrum. How do we define "error" and "mistake" in relation to "negligence"? Whose responsibility/obligation is it to inform the patient? What purpose is served by full disclosure? Is it always in the patient's best interest to know everything that has transpired? Will there consequences for those doctors who choose not to inform on their colleagues?

Consider the following more realistic examples:

1. You see a patient referred by your cash cow OB/Gyn with regards to a palpable breast mass. Upon review of last year's mammogram it appears that someone neglected to inform the patient that BiRADs IV calcifications were noted in the area where there is now a palpable mass. The mammogram had been ordered by the OB/Gyn. You've worked with the OB/Gyn for ten years and you've never had a situation where you questioned his management of a patient's care. He is universally recognized as an excellent physician and is well respected by the community. Moreover, he sends you at least 10-15 cases a month. What do you do?

2. You see a consult in the ICU for gallstone pancreatitis. The patient is in multiple organ failure and the CT scan suggests pancreatic necrosis. Upon reviewing the electronic medical record, you observe that the patient had been admitted multiple times over the past three years to the hospital by the internist for minor attacks of cholelithiasis and gallstone pancreatitis. A surgical evluation had never been requested. The internist has just finished a very emotional family meeting where he informed the wife and children of the patient's dire prognosis. Internist's eyes are swollen and red cracked. She has been the physician for everyone in this family for 15 years. Are you morally obligated to inform the family at this very delicate time that their trusted doc screwed up? Or ought you to show some tact and send them an anonymous letter in the mail three months later along with an attachment listing area malpractice attorneys?

3. You're the ID consultant seeing a patient with perianal sepsis. Cultures from the I&D site are growing MRSA. The general surgeon managing the case just has the patient on Unasyn. The cultures have been available in the chart for 4 days. You were consulted because the patient had persistent erythema and a leukocytosis. Do you simply make the necessary antibiotic adjustments? Or inform the patient that the general surgeon neglected to respond in an appropriate fashion to culture results that were freely available days ago?

First of all, if it's New Year's Eve and you find yourself at a dinner party where the dominant topic of discussion is medical ethics, it's probably safe to assume that you've made some sort of horrible mistake in choosing your dinner companions and you ought to explore all possible modes of escape from said gathering. I mean, it's New Year's Eve right? Let's drink some champagne and rant about the Browns and tell a few funny stories.

But an issue like this is generally handled in an overly simplified fashion. It's a nice little thought experiment and well reasoned arguments can be made for telling versus not telling but the reality of such situations is usually much more nuanced and complex. To aver that one ought to always inform a patient of a past error is dangerously rigid and dogmatic. Likewise, to maintain that you would never reveal such information to a patient only serves to create the impression that physicians just look out for each other and are not a patient's advocate.

It's not a black and white moral conundrum. How do we define "error" and "mistake" in relation to "negligence"? Whose responsibility/obligation is it to inform the patient? What purpose is served by full disclosure? Is it always in the patient's best interest to know everything that has transpired? Will there consequences for those doctors who choose not to inform on their colleagues?

Consider the following more realistic examples:

1. You see a patient referred by your cash cow OB/Gyn with regards to a palpable breast mass. Upon review of last year's mammogram it appears that someone neglected to inform the patient that BiRADs IV calcifications were noted in the area where there is now a palpable mass. The mammogram had been ordered by the OB/Gyn. You've worked with the OB/Gyn for ten years and you've never had a situation where you questioned his management of a patient's care. He is universally recognized as an excellent physician and is well respected by the community. Moreover, he sends you at least 10-15 cases a month. What do you do?

2. You see a consult in the ICU for gallstone pancreatitis. The patient is in multiple organ failure and the CT scan suggests pancreatic necrosis. Upon reviewing the electronic medical record, you observe that the patient had been admitted multiple times over the past three years to the hospital by the internist for minor attacks of cholelithiasis and gallstone pancreatitis. A surgical evluation had never been requested. The internist has just finished a very emotional family meeting where he informed the wife and children of the patient's dire prognosis. Internist's eyes are swollen and red cracked. She has been the physician for everyone in this family for 15 years. Are you morally obligated to inform the family at this very delicate time that their trusted doc screwed up? Or ought you to show some tact and send them an anonymous letter in the mail three months later along with an attachment listing area malpractice attorneys?

3. You're the ID consultant seeing a patient with perianal sepsis. Cultures from the I&D site are growing MRSA. The general surgeon managing the case just has the patient on Unasyn. The cultures have been available in the chart for 4 days. You were consulted because the patient had persistent erythema and a leukocytosis. Do you simply make the necessary antibiotic adjustments? Or inform the patient that the general surgeon neglected to respond in an appropriate fashion to culture results that were freely available days ago?

Friday, January 2, 2009

Rural Surgery

A nice article from the Washington Post (via KevinMD) last week about the impending general surgeon shortage in rural America. Here are some choice tidbits:

*In 1980, 980 general surgeons were trained in the the USA. In 2008, the number has reamined constant despite an increase in population by 79 million.

*Today there are only 5 general surgeons per 100,000 people

*Most rural general surgeons are over the age of 50

So this a good thing if you're a young general surgeon, right? There's going to be a huge demand to replace the retiring generation of surgeons and hospitals will need to reconstitute its forces. Because let's face it, surgeons are vital to a rural hospital's bottom line. The lucrative procedures that a local general surgeon can bring in often makes the difference between profitability and a hospital closing. Check out this power point presentation from the AAMC on rural surgery. Surgical services can potentially provide up to 30% of hospital revenue in the rural setting. Every time Podunk Hospital has to ship out an appendectomy or a hip fracture or a colon cancer because of surgeon unavailability, that's money lost.

But before we lose ourselves (we being young general surgeons) in rapturous expectations, there are some cold hard facts to digest. Namely, that in order to be a rural general surgeon, this means that you have to convince your spouse that it would be a great idea to move to Otsego, New York or Platteville, WI. You actually have to live in these towns. This isn't necessarily a bad thing, but you better be damn sure living the small town American life is what you really want. Secondly, rural surgery requires that one is comfortable performing certain procedures that most residents in training these days are not exposed to, i.e. setting minor fractures, hysterectomies, and ceasarean sections. Finally, although the hospital benefits enormously from successfully recruiting a general surgeon and will pay handsomely up front to do so, it can be difficult to maintain a suitably busy practice if you live in a town of 10,000. What happens is, the hospital will entice you to their sleepy hamlet with a seemingly exorbitant guaranteed contract (most general surgeons receive a steady deluge of junk emails from headhunters promising $350,000 a year or more guaranteed for the first three years, maybe with a large signing bonus on top of that). But when the guarantee runs out, you're on your own. And if you live in a town with, say, three primary care practices, it's going to be hard to maintain the sort of volume that will sustain your previous income level. You may find you are only doing 5 or 6 cases a week without a reasonable expectation of growth (given the population) and your income falls by 50% or more. It happens. And the hospitals don't care because they're still racking in the procedural profits from the cases you do book.

So be careful. Be wary of those glossy post cards that come in the mail with a picture of a moose and some mountains and a burbling stream in the background promising half a million bucks to start if only you come to this "quaint little midwestern bedroom community" that is only "a short drive to a major metropolitan area" (i.e. 3 hours to Dayton, OH) and is perfect for the "hunting and fishing enthusiast."

I think the answer to the problem is two-fold:

1. Loan forgiveness for surgical residents willing to commit to the backwoods of America (much like I propose loan forgiveness as a way to increase the number of medical students who opt for a career in primary care).

2. The creation of a dedicated specialty of "rural surgery" where more attention is given to the learning of OB/Gyn, endoscopy, and orthopedics. We have fellowships for "advanced laparoscopy" that didn't exist five years ago. The field of "trauma surgery' has become so non-operative that now trauma surgeons are looking to cherry pick late night emergency cases. Surgical training is constantly in flux. Rural surgery is the obvious next field for potential growth....

Thursday, January 1, 2009

Best Movie of 2008

I'm going to go off the reservation a little bit here (I can do that on MY blog) and write a movie review. The last one I did (almost exactly a year ago) was about No Country for Old Men and it wasn't exactly laudatory. This time I have good things to say about a Hollywood production. Here it goes: WALL-E is hands down the best American movie of the year. That's right, I'm claiming that a hyper-modern, next generation cartoon from the Pixar people who gave us Toy Story ought to win the Best Picture award this March. And it shouldn't even be close.

Since my wife is pregnant and I was on call, our New Year's Eve game plan was to rent a couple movies and set up shop on the couch. WALL-E had arrived in the mail from Netflix a few days prior so I said what the hell. If we hated it, we also had Hancock as a back-up plan. Turns out we made the right decision.

WALL-E, being a Pixar production, gives you that quasi cartoony/realistic feel that was mastered in the technical excellence of Shrek and Finding Nemo. Now, I found Nemo to be fun, mindless entertainment. But I wouldn't watch it again. The story was predictable and overly sentimental and rather formulaic. And I'm not an Ellen Degeneres fan. And Shrek, funny and stimulating as it was, struck me as a little mean spirited and overly ironic, weighed down by cheap gags and easy sarcasm. WALL-E's aspirations are much more modest.

WALL-E presents an apocalyptic vison of a future earth devastated and scorched by the wasteful misdeeds of now absent humans. We meet WALL-E, a trash compacting robot, alone on a ravaged, sered planet, building skyscrapers of cuboidal compacted detritus. During his labors, he collects certain items of interest and stores them at his trash bin compound, a wasteland Smithsonian of Americana and nostalgia. The first half hour of the flick is a majestic display of subtle characterization and wit. More individuality and humanity is wrung out of 30 minutes of this mute little robot buzzing around the barren landscape that one can find in the the entire oevre of Brad Pitt. The visual effects are also astounding. The dried-out brown riverbeds look like furrows clawed into the clay by giant talons. I could have watched WALL-E compact trash alone with his cockroach companion all night.

But the story must go on. WALL-E's world is disrupted by the arrival of EVE, a robot drone sent from a mothership in space to search for signs of life on earth. Of course WALL-E falls in love with EVE, prompted by his repeated viewings of a scene from "Hello Dolly". With his help, she finds a single plant sprout and he smittenly follows her back to her ship. And this is where we find out about the humans. They've all turned into sedentary, morbidly obese tubs of lard who jet around in these automatic self-propelled luxury lazy boys with a giant entertainment screen projected in front of their faces at all times, deluged by products and ads and vapid amusement. It's a vaguely totalitarian society, albeit the less frightening kind (Brave New World vs. Nazi Germany). The satire on American consumerist society and selfishness is especially biting given the recent turn of events on Wall Street. The bad robots who run things don't want the humans to find out about the vegetation; as a result, EVE and WALL-E are identified as rogues and adventures ensue.

Ultimately, order is restored, the humans return to earth and EVE realizes her "feelings' for the indomitable, doting WALL-E and everything ends happily ever after. I know, I know, it sounds mawkish and maudlin but somehow it isn't. There is a simple earnestness to this movie that is rare in our current times. Whether in real life or in the arts, we have been induced to think that ironic detachment is the supreme state of mind. And now a pervasive irony "tyrannizes" us, says David Foster Wallace. It's considered gauche to believe that authentic feelings and emotions are possible. Love and respect and awe are all placed under the microscopic eye of bemused irony. It's a dark road that we travel down. Thus we see the celebration of such things as Seinfieldian irreverence and soulless superficiality and the mean-spirited Hollywood blogs and the proliferation of brutally graphic violence and sex in our movies. We saw a pointless exercise in meaninglessness like No Country for Old Men garner a pile of Academy Awards last year. This year we may very well see Heath Ledger rewarded with a best actor Oscar for the protrayal of a vicious, amoral, anarchist in the Dark Knight.

To be earnest about the human condition is now grounds for ridicule, apparently. We are now conditioned to question our spontaneous emotional responses to situations. Is it ok to cry at the funeral of a loved one? Will someone overanalyze the shudders of my shoulders as I sob and make a joke of it? Can I be privately moved by the way my wife laughs at slapstick comedy when she doesn't know I'm looking? Is it ok to get excited about a child's glee on Christmas morning? This is where we're heading. And it doesn't need to be this way. It's ok to mean what we say, unconditionally. It's ok to feel anger or fear or love. Some things in life are hallowed and ought not to be subjected to the aloof appraisals of irony and cynicism. Life is dark enough; we don't need the Dark Knight and his critically acclaimed nemesis to remind us of this. Sometimes, the sight of two robots holding hands on a desolate wasteland is plenty sufficient.....

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)