Good article in Archives here about inadequate lymph node harvests in colorectal cancer surgery.

One of the yardsticks for assessing the quality and oncologic adequacy of a surgical resection for colon cancer is to determine the number of lymph nodes harvested with the specimen. Lymph node status determines staging of the tumor and the need for adjuvant chemotherapy. We like to see at least 12 nodes in the specimen in order to state with confidence that a tumor is either node negative or node positive. Assessing fewer than 12 nodes risks understaging the disease and suggests the need for chemotherapy even if the seven or eight nodes available are negative. It also is construed as proof of "inadequate surgical resection" in many academic circles.

This paper suggests otherwise. Lymph node harvesting is affected by multiple factors including patient age, tumor stage, location of tumor in the colon, and the year the surgery was performed. Attributing a failure to harvest at least 12 nodes solely to the performing surgeon is overly presumptive.

I can attest to the findings of this paper. As surgeons, we've all done low anterior resections for a rectosigmoid tumor via the total mesorectal excision technique that completely cleans out the pelvis only to find that on the path report, only ten nodes were seen. It's disappointing but what can you do? There isn't anything else to cut out, other than to go back in there and start scraping against the sacrum with a rake. You know you've done an adequate oncologic resection but the cold hard numbers suggest some sort of failure. Papers like this perhaps will help attentuate some of the blame mentality (patient should have seen me, I always harvest 12 nodes!) that occurs within the surgical community...

Wednesday, December 30, 2009

The False Lobby

Further evidence that the AMA does not represent the vast majority of physicians in this country--- in a letter to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid about HR bill 3590, they give their grudging provisional support to the overall bill albeit with a few recommendations for improvement.

One thing they disapprove of is the proposal to levy an excise tax on all medical and surgical cosmetic procedures.

Missing from the list of "improvements" is any mention at all of tort reform or a demand for better reimbursement of cognitive medicine. Nor is there any call for subsidization of medical school costs for students pursuing a career in primary care or general surgery.

Yeah, elective plastic surgery is an untouchable. But tort reform? Reimbursement reform? Not worth it, apparently.

Keep trying JJ Rohack MD. We're waiting...

One thing they disapprove of is the proposal to levy an excise tax on all medical and surgical cosmetic procedures.

Missing from the list of "improvements" is any mention at all of tort reform or a demand for better reimbursement of cognitive medicine. Nor is there any call for subsidization of medical school costs for students pursuing a career in primary care or general surgery.

Yeah, elective plastic surgery is an untouchable. But tort reform? Reimbursement reform? Not worth it, apparently.

Keep trying JJ Rohack MD. We're waiting...

Sunday, December 27, 2009

Reassessing the Dartmouth Data

Great article from the NY Times over the weekend that challenges some of the conventional wisdom stemming from the Dartmouth Atlas data; i.e. that some hospitals spend twice as much on health care as others without seeing any signficant benefit in outcomes. In probably the most famous health care essay of 2009, Atul Gawande used the Dartmouth data (along with a weekend junket spent eating spicy chili and chicken wings with doctors in McAllen, TX) as a springboard to jump to the conclusion that this discrepancy in spending is a function of the fact that there are some places in America where doctors and hospitals are greedy profit whores who will order needless tests and perform unnecessary procedures all for the sake of MONEY.

The good folks at UCLA Medical Center were one of the hospital systems targeted by Peter Orszag et al as a shining example of the culture of waste and greed that afflicts American health care delivery. And they didn't appreciate the implied censure so much. So they did some research of their own, specifically on those patients with advanced heart failure. What they found is that when you include all patients in the study, not just those who ended up dying, then mortality rates are lower in those California teaching hospitals where resource expenditures are higher. Furthermore, other research has demonstrated that a hospital system's costs are intimately associated with the socioeconomic distribution of its patient population (i.e. lily white Rochester MN provides the Mayo Clinic with a healthier cohort of patients, hence costs are going to be lower than a place like McAllen with its high incidence of obesity, hyperlipidemia, and atherosclerosis.)

The bottom line is that there is no black and white solution to the cost conundrum. Sometimes it's in society's best interest to spend as much as possible on certain patients (let's arbitrarily say ages 30-55) who are not only salvaged, but returned to society as functional entities with aggressive, invasive modern medical intervention. Sometimes, cost depends on the kinds of patients a hospital services. Sometimes it all depends on how data is construed and interpreted.

But it would be a disservice to places like UCLA to simply aver that all our cost problems can be solved if only everyone would "start acting more like Mayo and the Cleveland Clinic". It's far more complex than that. End of life care is a not just an economic issue, it's a moral one. And it's not clear that we as a society are willing or able to start wading into the murky waters of such a moral interrogation. It's far easier to go with the talking point zinger (be more like Mayo!) than to start delving into the hard questions and decisions about terminal care and rationing and the notion of identity/social worth in futile cases.

The good folks at UCLA Medical Center were one of the hospital systems targeted by Peter Orszag et al as a shining example of the culture of waste and greed that afflicts American health care delivery. And they didn't appreciate the implied censure so much. So they did some research of their own, specifically on those patients with advanced heart failure. What they found is that when you include all patients in the study, not just those who ended up dying, then mortality rates are lower in those California teaching hospitals where resource expenditures are higher. Furthermore, other research has demonstrated that a hospital system's costs are intimately associated with the socioeconomic distribution of its patient population (i.e. lily white Rochester MN provides the Mayo Clinic with a healthier cohort of patients, hence costs are going to be lower than a place like McAllen with its high incidence of obesity, hyperlipidemia, and atherosclerosis.)

The bottom line is that there is no black and white solution to the cost conundrum. Sometimes it's in society's best interest to spend as much as possible on certain patients (let's arbitrarily say ages 30-55) who are not only salvaged, but returned to society as functional entities with aggressive, invasive modern medical intervention. Sometimes, cost depends on the kinds of patients a hospital services. Sometimes it all depends on how data is construed and interpreted.

But it would be a disservice to places like UCLA to simply aver that all our cost problems can be solved if only everyone would "start acting more like Mayo and the Cleveland Clinic". It's far more complex than that. End of life care is a not just an economic issue, it's a moral one. And it's not clear that we as a society are willing or able to start wading into the murky waters of such a moral interrogation. It's far easier to go with the talking point zinger (be more like Mayo!) than to start delving into the hard questions and decisions about terminal care and rationing and the notion of identity/social worth in futile cases.

Saturday, December 26, 2009

Outsourcing health care?

Dr Scott Gottlieb had a piece in the WSJ yesterday about the threat posed to physicians with coming health care reform. This paragraph jumped out at me:

And I'm wondering, why is this a bad thing? Shall we continue with the status quo of unabated mass-consults where a patient gets admitted to an internist's service and ends up with consults from surgery, GI, ID, and renal; all for a demented little nursing home lady? Financial pressures have a way of altering behavior the fastest. The fee-for-service quandary is contingent on the referral patterns of primary care doctors. The more they are penalized for farming out complicated patients to subspecialists, the less likely that clinical paradigm will continue. And I'm not talking about the patient with appendicitis or the older guy with guiac positive stools. Those patients justifiably need specialist consultation. But does every type II diabetic need an endocrinologist? Does ever obese patient with rickety knees need referral to an orthopod for joint replacement? Does every patient with a perianal abscess need an Infectious Disease consult?

There's plenty to go after in this unwieldy health care reform bill, but this isn't one of them...

Primary-care doctors who refer patients to specialists will face financial penalties under the plan. Doctors will see 5% of their Medicare pay cut when their "aggregated" use of resources is "at or above the 90th percentile of national utilization," according to the chairman's mark of Section 3003 of the bill. Doctors will feel financial pressure to limit referrals to costly specialists like surgeons, since these penalties will put the referring physician on the hook for the cost of the referral and perhaps any resulting procedures.

And I'm wondering, why is this a bad thing? Shall we continue with the status quo of unabated mass-consults where a patient gets admitted to an internist's service and ends up with consults from surgery, GI, ID, and renal; all for a demented little nursing home lady? Financial pressures have a way of altering behavior the fastest. The fee-for-service quandary is contingent on the referral patterns of primary care doctors. The more they are penalized for farming out complicated patients to subspecialists, the less likely that clinical paradigm will continue. And I'm not talking about the patient with appendicitis or the older guy with guiac positive stools. Those patients justifiably need specialist consultation. But does every type II diabetic need an endocrinologist? Does ever obese patient with rickety knees need referral to an orthopod for joint replacement? Does every patient with a perianal abscess need an Infectious Disease consult?

There's plenty to go after in this unwieldy health care reform bill, but this isn't one of them...

Wednesday, December 23, 2009

Portacath Insertion Technique

(Via Medscape)

There's an article in the British Journal of Surgery this month comparing two techniques of portacath insertion; the Seldinger technique vs. the venous cutdown. Portacaths are the little subcutaneous thingies that are used for chemotherapy infusions. Instead of having all your arm veins ravaged by the toxic chemicals of adjuvant chemotherapy, one can choose to have a port placed, thereby facilitating access to one of the main central veins.

Traditionally portacaths are placed as an outpatient surgical procedure using some IV sedation and local anesthetic. The majority of them are placed using the Seldinger technique whereby you jam a big fat needle into either the internal jugular in the neck or under the clavicle and into the subclavian vein, slide a guidewire through the bore of the needle and then advance the catheter to the SVC over the wire. The catheter is then tunneled subcutaneously for a bit and hooked up to a port, usually situated somewhere on the upper chest wall.

I generally don't do mine that way. Most of the time (95%) I utilize the venous cutdown method. I make a small incision over the deltopectoral groove, dissect out the cephalic vein, make a venotomy, and directly insert the catheter into the vein. The rest follows as per the Seldinger technique. It takes me about 10-20 minutes, usually. I do it without an assistant. There's no need for a CXR afterwards in the PACU. It's an elegant procedure when all goes perfectly.

Why do I choose to cutdown? Well, anytime you start jabbing large bored needles into someone's neck or chest wall, you assume a certain amount of risk; specifically pneumothorax, hemothorax, accessing the artery rather than the vein, etc. Granted, these complications don't occur very often (1-3% risk is usually quoted), but a typical general surgeons accumulates enough numbers over a career that inevitably he/she will have to deal with them at some point.

The cutdown eliminates the possibility of a lot of these complications. I don't have to worry about pneumothoraces. I don't have to worry that the blood I draw back on my needle stick is maybe arterial blood rather than venous (is it too red???). And it doesn't take me any longer than the guys who do the Seldinger technique.

The article alluded to seems to suggest that the cutdown is an inferior technique. And it's a decent article---randomized controlled trial and all that jazz. The data, the science, seems to suggest that the cutdown isn't any safer and, furthermore, it takes longer to perform. So what do I do with that information? Do I change my technique, to better accomodate myself to the "best available evidence"? Am I making myself liable if one of my ports becomes infected or gets clogged after a few months?

I can do a subclavian stick. I put central lines in quite a bit for post op sick patients and as a favor for my medicine colleagues. I prefer the subclavian over the jugular. I'm not afraid of the procedure. I think I'm adept at the technique. But for an elective case on a patient who has enough to worry about (recent diagnosis of cancer, uncertainty of the side effects of the anticipated chemotherapy) I want to use the technique that completely eliminates the possibility that a major complication could occur. Science be damned...

Conservative Incoherence

Matthew Yglesias (usually a little too bleeding heart liberal for my tastes) has a good point today about modern Conservative (i.e the party of Limbaugh and Palin) objections to health care reform, specifically the Independent Medical Advisory Council. In its current iteration IMAC would function as a federal sieve to prevent wasteful spending on medical interventions and treatments not proven to be efficacious. It's supposed to be an independent board of doctors and health care professionals who make decisions based on best available evidence. Seems reasonable right?

Sarah Palin, in her by now trademark unhinged outrageous obliviousness of the truth, revisits the idea of this somehow being a variation of the dreaded "death panels" she ranted about during the summer (never mind that they never existed to begin with).

Here's the problem: IMAC is related to Medicare spending (you know, the gargantuan federal entitlement program). One would think that someone of a conservative bent, someone from a limited government, reduced federal spending frame of mind would be all in favor of an independent private council that sought to limit federal spending on healthcare. But coherence and truth are always trumped by partisanship and the possibility of scoring cheap political points in today's Republican Party...alas..

Sarah Palin, in her by now trademark unhinged outrageous obliviousness of the truth, revisits the idea of this somehow being a variation of the dreaded "death panels" she ranted about during the summer (never mind that they never existed to begin with).

Here's the problem: IMAC is related to Medicare spending (you know, the gargantuan federal entitlement program). One would think that someone of a conservative bent, someone from a limited government, reduced federal spending frame of mind would be all in favor of an independent private council that sought to limit federal spending on healthcare. But coherence and truth are always trumped by partisanship and the possibility of scoring cheap political points in today's Republican Party...alas..

Northwestern Cardiac Controversy

Great article in today's WSJ (need to be a subscriber to read, or just buy the damn hard copy) about a brewing scandal at Northwestern University involving a cardiothoracic surgeon, a cardiologist, the medical device industry, and the FDA. Essentially, the prominent CT surgeon, Dr. Patrick McCarthy, was implanting mitral valve prostheses into patients that had not been specifically approved by the FDA. Ultimately, the valve components were approved in retrospect, as happens often in medical technology. But the device was invented by Dr. McCarthy himself and he was working on compiling a series of patients for a case report eventually published in a major medical journal.

The controversey erupted when one of his valve patients developed complications and kept returning to the hospital with heart failure exacerbations. The patient's cardiologist, Dr. Nalini Rajamannan, did some investigating and was able to discover that the valve implanted in her patient had not been FDA approved at the time of surgery. So she enlists the help of an old college lawyer friend to represent the patient (who eventually had to have the device replaced in another surgery at the Ckeveland Clinic) in a malpractice lawsuit. Just to spice things up, and to quash any notion that Dr. Rajamannan is some selfless noble crusader who simply seeks justice for a wronged patient, her attorneys also submitted a list of demands to Northwestern University including such things as a multi-million dollar endowed professorship for herself, the firing of certain Northwestern empoyees, and the deposit of $1 million into her private retirement account!

Now beyond all the salaciousness and tabloid-esque personal enmity of such a story, a basic philosophical element of medical innovation is illuminated. At what point can we universally state that a new medical innovation has met the standards of rigorous testing and can safely substitute for previous modes of therapy? Laparoscopic surgery developed on the fly. No one knew how risky the surgery would be until enough patients (human guinea pigs?) had been accumulated in actual practice to determine statistical efficacy. New orthopedic components, although FDA approved, are routinely implanted into real live patients without knowing for sure that they will function as well as previous components. Laparoscopic for colorectal cancer was an experiment. No one knew if outcomes were going to be comparable with the open technique. Medicine demands testing the unknown, doubting previously held dogma.

Certainly it seems that the arrogant Dr McCarthy could have been more forthright about the fact he was implanting non-approved, but groundbreaking, rigorously tested valves into his patients. Communication and honesty have been proven over and over to be the foundation of the doctor/patient relationship and violation of this ethic is what leads to anger and malpractice suits. But when we allow patients to define themselves as victims of experimentation rather than as beneficiaries of novel medical innovations, then this country is bound to lose its place as the worldwide leader in biotech breakthroughs....

The controversey erupted when one of his valve patients developed complications and kept returning to the hospital with heart failure exacerbations. The patient's cardiologist, Dr. Nalini Rajamannan, did some investigating and was able to discover that the valve implanted in her patient had not been FDA approved at the time of surgery. So she enlists the help of an old college lawyer friend to represent the patient (who eventually had to have the device replaced in another surgery at the Ckeveland Clinic) in a malpractice lawsuit. Just to spice things up, and to quash any notion that Dr. Rajamannan is some selfless noble crusader who simply seeks justice for a wronged patient, her attorneys also submitted a list of demands to Northwestern University including such things as a multi-million dollar endowed professorship for herself, the firing of certain Northwestern empoyees, and the deposit of $1 million into her private retirement account!

Now beyond all the salaciousness and tabloid-esque personal enmity of such a story, a basic philosophical element of medical innovation is illuminated. At what point can we universally state that a new medical innovation has met the standards of rigorous testing and can safely substitute for previous modes of therapy? Laparoscopic surgery developed on the fly. No one knew how risky the surgery would be until enough patients (human guinea pigs?) had been accumulated in actual practice to determine statistical efficacy. New orthopedic components, although FDA approved, are routinely implanted into real live patients without knowing for sure that they will function as well as previous components. Laparoscopic for colorectal cancer was an experiment. No one knew if outcomes were going to be comparable with the open technique. Medicine demands testing the unknown, doubting previously held dogma.

Certainly it seems that the arrogant Dr McCarthy could have been more forthright about the fact he was implanting non-approved, but groundbreaking, rigorously tested valves into his patients. Communication and honesty have been proven over and over to be the foundation of the doctor/patient relationship and violation of this ethic is what leads to anger and malpractice suits. But when we allow patients to define themselves as victims of experimentation rather than as beneficiaries of novel medical innovations, then this country is bound to lose its place as the worldwide leader in biotech breakthroughs....

Tuesday, December 22, 2009

Night time gallbladders

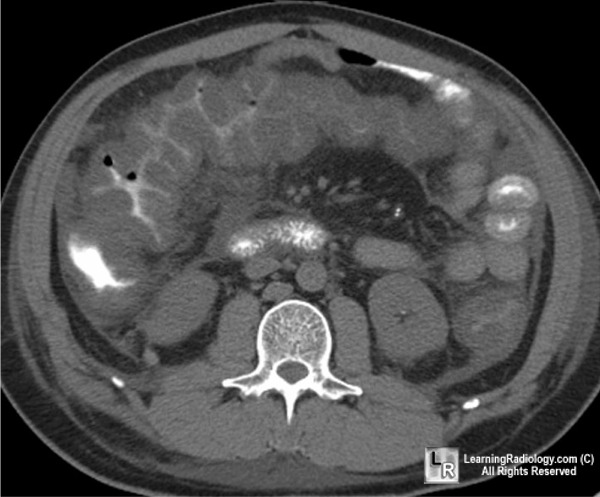

I usually don't do laparoscopic cholecysyectomies in the middle of the night. Rare is the case you can't just hydrate, put on antibiotics overnight and operate the next day. But this guy needed emergent surgery; septic, confused, white count near 30,000. The gallbladder was basically dead; a flaccid, ashy-hued mishmash of once vibrant tissue. Furthermore, the edema from the inflammation was so intense, the right colon was being compressed (see CT) leading to significant cecal dilatation.

Cases like this usually go suprisingly smoothly, even with the laparoscope, because the inflammatory reaction allows for easy dissection of anatomic planes. Two days later he was eating pizza and asking when the hell I was going to let him go home. He had Christmas presents to buy.

Thursday, December 17, 2009

AMA Sell-out

The eminent J. (Josiah?) James Rohack MD has a post at KevinMD, updating us on the current stance of the AMA toward the health care reform bills swirling around Congress. Read it if you like. It's a very interesting piece, to say the least. He delineates several aspects of the bills that could stand a little improvement but fails to comment whatsoever on the absence of any significant tort reform measures in the proposed pieces of legislation. That's astounding. Ask any physician what needs to be fixed in American health care and tort reform will be somewhere in the top three. It's truly an amazingly contemptuous act of arrogance to write up something like this without even acknowledging the one aspect of reform that doctors universally would like to see enacted.

Any shred of credibility the AMA had as the "voice of American physicians" is now officially gone. JJ Rohack, thank you for making it crystal clear. Perfidious, ineffectual and tone deaf is no way to go through life as a physician lobbying organization, good sir.

Wednesday, December 16, 2009

Coumadin and Afib in the Elderly

I cover trauma call for the eastern suburbs of Cleveland at a level II trauma center. Given our patient population, we don't exactly see the Friday Night Gun Club sorts of cases like one would experience at level I urban centers. Ours is more like the Saturday Afternoon Fall Down and Bump Your Head Club. Other than blunt trauma from MVC's, our next most popular mechanism of injury is some little old lady or little old gentleman losing balance, and whacking his/her dome against the floor.

What I find annoying is the high percentage of these elderly patients (many in their 80's and 90's) who are on anti-coagulation therapy for atrial fibrillation. This buys the injured patient a ticket to the ICU and multiple CT scan to make sure there is no delayed intracerebral bleeding. Mucho dinero. Even more annoying is the fact a lot of these people are frequent flyers. You browse through the computer chart and you see three or four admissions over a 2 year period for similar falls.

The rationale behind anti-coagulating people with atrial fibrillation is that you want to reduce the risk of clot formation in the fibrillating heart chambers and subsequent embolic stroke. There's a fairly recent RCT from Scotland (the BAFTA study) that seemed to support the use of coumadin over aspirin even in elderly patients (>75) with afib. But the data showed that, despite the use coumadin, there was still a 1.8% risk of stroke over the course of one year. And the trial didn't use a control of patients without any anti-coagulation; it just compared coumadin versus aspirin.

I find it difficult to wrap my mind around the idea that anybody over the age of 85 needs to be on coumadin for afib. Not because of rationing, mind you, but simply for safety reasons. It's not clear to me that the benefit outweighs the risks, even in the most optimal candidates. Certainly anyone with a history of prior falls, dementia, or a GI bleeding history ought to be excluded; but in this era of fragmented care (hospitalists and subspecialists and lack of communication) it gets harder and harder to make sure that we aren't just mindlessly implementing "best practice recommendations" without looking at the individual patient...

What I find annoying is the high percentage of these elderly patients (many in their 80's and 90's) who are on anti-coagulation therapy for atrial fibrillation. This buys the injured patient a ticket to the ICU and multiple CT scan to make sure there is no delayed intracerebral bleeding. Mucho dinero. Even more annoying is the fact a lot of these people are frequent flyers. You browse through the computer chart and you see three or four admissions over a 2 year period for similar falls.

The rationale behind anti-coagulating people with atrial fibrillation is that you want to reduce the risk of clot formation in the fibrillating heart chambers and subsequent embolic stroke. There's a fairly recent RCT from Scotland (the BAFTA study) that seemed to support the use of coumadin over aspirin even in elderly patients (>75) with afib. But the data showed that, despite the use coumadin, there was still a 1.8% risk of stroke over the course of one year. And the trial didn't use a control of patients without any anti-coagulation; it just compared coumadin versus aspirin.

I find it difficult to wrap my mind around the idea that anybody over the age of 85 needs to be on coumadin for afib. Not because of rationing, mind you, but simply for safety reasons. It's not clear to me that the benefit outweighs the risks, even in the most optimal candidates. Certainly anyone with a history of prior falls, dementia, or a GI bleeding history ought to be excluded; but in this era of fragmented care (hospitalists and subspecialists and lack of communication) it gets harder and harder to make sure that we aren't just mindlessly implementing "best practice recommendations" without looking at the individual patient...

Got Exploitation?

The inimitably shameless Sean Hannity prodding family members of 9/11 victims to accuse President Obama of treason....for daring to prosecute Al Qaeda asshole KSK in a court of law.....

What is it that the right winger nutjobs are afraid of? That we cannot trust our legal system or law enforcement institutions to carry out justice? That KSK will spout ludicrous jihad nonsense? That the only recourse when faced with absolute evil is to betray our founding principles? These guys like Hannity love to foment this culture of fear for some reason. The more afraid the American population is, the easier it is to justify torture and other sundry violations of an open democratic society...

What is it that the right winger nutjobs are afraid of? That we cannot trust our legal system or law enforcement institutions to carry out justice? That KSK will spout ludicrous jihad nonsense? That the only recourse when faced with absolute evil is to betray our founding principles? These guys like Hannity love to foment this culture of fear for some reason. The more afraid the American population is, the easier it is to justify torture and other sundry violations of an open democratic society...

Tuesday, December 15, 2009

Bad Ass

Ex vivo cancer surgery from Dr Kato at Columbia on a giant liposarcoma invading liver/pancreas/stomach. (NY Times)

Monday, December 14, 2009

Peterson's Defect

This was tricky. A middle aged lady ten years status post laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery (Roux en Y configuration) presented with crampy abdominal pain and nausea. Her plain films showed multiple dilated loops of small bowel. So I got a CT scan to better delineate the anatomy.

Bowel obstructions in Roux-n-Y gastric bypass patients always make me a little nervous. As opposed to garden variety, adhesion-mediated obstructions in people with normal anatomy, conservative treatment often fails in these patients. For one thing, you cannot adequately decompress them with nasogastric suction. Furthermore, the incidence of internal hernias is much higher, owing to the altered anatomy of the procedure (roux limbs and split mesenteries etc). So going into these cases, your threshold for surgery has to be exponentially higher than normal.

The scan above shows a subtle spiralling of some small bowel mesenteric vessels in the area where one would normally find the jejunojejunal anastomosis. Single views don't do the pathology justice; you really have to be able to scroll up and down through the loops of bowel on the scan. The patient looked uncomfortable, was tender, and I just didn't feel like dicking around for much longer. So I explored her in the OR.

She'd had two previous surgeries, prior to her gastric bypass even, for bowel obstructions secondary to an old hysterectomy, so things were pretty confusing, anatomically speaking, when I first entered her peritoneal cavity. The jejunojejunostomy appeared to be corkscrewed. That was clear enough from the beginning. Then I identified a decompressed limb of bowel going up to the gastric pouch (roux limb, a ha!). And then it looked like a bunch of small bowel had slipped through a space between the roux limb and the transverse mesocolon---classic Petersen's defect. Unfortunately, however, the bowel didn't want to slide back out of the space right away. It was stuck somewhere else further downstream. So I basically had to perform a full adhesiolysis of bowel, starting from terminal ileum and working back. To keep things organized, I literally had to place identifying stitches in the serosa of the proximal bowel as I flipped things back and forth. A couple of times it got a little hairy as the bowel started to turn bluish and I had to reverse my maneuvers, untwist things the correct way. Finally I freed everything up and the bulk of the small bowel was liberated, came rushing out from behind the defect. Looking down, the J-J anastomosis was normal again, the corkscrew configuration gone. I closed the defect, put in some voodoo-ish anti-adhesive Seprafilm and got the hell out.

Sunday, December 13, 2009

Aggie Medicine?

Atul Gawande has a new health policy piece in the New Yorker this week. At issue is the problem of cost control and how the health care bills swirling around Washington DC fail to adequately account for the exponential growth in health care spending anticipated based on current trends and the fact that an expected 94% of Americans will be covered by the new legislation.

Gawande:

If nothing is done, the United States is on track to spend an unimaginable ten trillion dollars more on health care in the next decade than it currently spends, hobbling government, growth, and employment. Where we crave sweeping transformation, however, all the current bill offers is those pilot programs, a battery of small-scale experiments. The strategy seems hopelessly inadequate to solve a problem of this magnitude. And yet—here’s the interesting thing—history suggests otherwise.

He proceeds to spend the bulk of the rest of the piece elucidating an analogy between health care reform and agricultural reforms that occured in the late 19th century in America and how these patchwork pilot programs can be a useful means to achieving meaningful reform. I sort of, kind of get it but it's a false analogy. The efforts of the US Department of Agriculture resulted in more efficient farms, consolidation of wasteful tracts of arable land, and provided a safety net (in the form of farm subsidies) for farmers to account for droughts and variations in demand. So not only did consumers make out (lower prices, surplus of goods), but the farmers and eventually the giant agroconglomerates also benefitted.

And that's where the analogy with medicine falls on its face. The pilot programs contained in the bill are designed to benefit patients and insurance companies and federal entitlements like Medicare in the form of lowering costs. And how is this accomplished? Basically by lowering reimbursements to providers and hospitals. Bundled payments, tiered rewards based on outcomes, elimination of fee-for-service are all worthy ideas to try; but the people entrusted with carrying out these reforms (doctors!) dont stand to benefit. It's a crude, cynical formulation I know. But we're only human. There has to be at least a morsel, a sliver of carrot hanging out there. It can't be all stick. I'm not saying doctors won't play ball. We will. But there has to be something for us to nibble at in this gargantuan bill. Mix in a little tort reform, medical school loan forgiveness, and subsidies for those who choose to practice in rural/low population areas (the present pilot program written into the bill is woefully inadequate) and I'm all for it. I'll even work for salary like the smart doctors at Mayo and Harvard with their fancy collaborative care models.

Roll with those punches

I couldn't imagine being a doctor if I weren't a general surgeon. I knew after a week of my third year med school surgery rotation that I was destined to be a surgeon. Not destined in some phony, overblown Knights of King Arthur's Court sense, but destined in the realistic sense that I probably could not have enjoyed a long career in medicine doing anything else. No other specialty gave me the same heightened rush, the same zest for labor, the same excitement to get back to the hospital as soon as possible. In other words, no other specialty untapped my inchoate desire to tranform myself into a psychopathic workaholic. The idea of instantly alleviating a patient's suffering through invasive, mechanical intervention is an intoxicating elixir for the idealistic, type A young people that surgery tends to attract. You might call it a form of the "hero-complex"; we get off on marching into a room, diagnosing the problem and implementing a plan that will almost immediately lead to the reversal of the patient's physical maladies. It's a cool rush.

But there's a balancing counterpoise to the thrill of heroism. The things we do as surgeons to our patients are saddled with the weight of potential complications. An ICU nurse I know always asks me if I've "committed any surgery on people today". She's kidding of course (at least she better be!), but her comment is tinged with an element of truth. It's an act of controlled violence, surgery, and the consequences of that act are unpredictable. We do the best we can. Any surgeon will tell you that. There's never intent to harm a patient but once that scalpel slaps into our palm, we knowingly take on the burden of ultimately realizing a suboptimal outcome, an outcome that is a direct consequence of the maneuvers we are about to perform. That's life as a surgeon. One out of every 450 gallbladders we do will result in a major bile duct complication. 8-10% of all colorectal anastomoses we perform will leak, to varying degrees of severity. Wound infections will plague 10-15% of our laparotomy incisions. One to five out of every 100 inguinal hernia repairs we do will fail. 3% of those patients who undergo a Whipple for pancreatic cancer won't walk out of the hospital alive. About 5% of patients undergoing thyroid surgery will sustain an injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, with 20% of these patients suffering permanent voice damage. It's a minefield of cold hard statistics we navigate through each and every day.

I suppose most doctors deal with it, this sense of guilt that develops when something goes wrong. But I doubt anyone bears a greater burden than the surgeon. The internist (assuming not a careless ass) knows deep down in her heart that she prescribed all the correct medications, listened to her patient's complaints, diagnosed everything correctly. She can take some solace in the fact the patient was not entirely compliant, or had a horrible family history of cardiac disease, or maybe just developed some ridiculously rare metabolic disease that any doctor would have struggled to diagnose. It's not so easy to rationalize when you've just operated on someone and they don't do well. The second guessing never stops, incessantly tormenting your sleepless nights, heart racing, pacing the darkened halls of your house, desperately trying to visualize from the depths of memory the moment in time during the operation when you cut this or sutured that, searching to no avail for that instant when you could have done something better, another stitch, a different technique, another instrument, a sign or symptom you missed, a less risky maneuver, something, anything that would have prevented the current state of affairs, your patient in the ICU, frightened, worse off for the moment than she was before the surgery. We all have these cases. Every surgeon has complications and bad outcomes. The ones that deny it are either liars or they don't operate nearly enough.

I remember a patient specifically from my early career. Three weeks after I started as an attending surgeon I was called on a Sunday to see an elderly guy with a bad bowel obstruction. His white count was elevated and the nurse mentioned he was having a lot of pain so I came in to see him. He certainly had an acute abdomen and, in reviewing the CT scan, he had all the pathognomonic findings of a rare entity known as gallstone ileus (pneumobilia, calcified mass in the terminal ileum). What happens is, a large stone from the gallbladder over time erodes into the duodenum creating a wide mouthed fistula between the biliary and intestinal tracts. The stone drops into the duodenum and migrates slowly downstream. Eventually it wedges itself into a spot in the bowel where it can't go any further, usually in the terminal ileum or ileocecal valve. The result is a high grade small bowel obstruction. The only solution is an operation. Classic surgical dogma teaches that your agenda during the operation is simply to alleviate the bowel obstruction. Take out the stone, do a limited small bowel resection, whatever is necessary. As for the gallbladder and any other potential stones, you were supposed to defer that battle for another day. When I was a chief resident, however, I had read some newer literature suggesting that, in the event the patient was stable and didn't have too many other co-morbidities, it would be reasonable to pursue the source of the pathology (cholecystectomy) during the same operation. So I fixed the bowel obstruction and we'd only been under anesthesia for about twenty minutes. I noted that the patient seemed stable. His vitals were rock solid. His past medical history was pretty unremarkable; no heart disease to speak of. So I rearranged my retractors and took a look up near the liver. Everything seemed somewhat scarred down and distorted. Seconds after placing the retractor to heft the edge of the liver up out of the way, my heart sank as a rush of green bile filled the operative field. What happened was that a very small, fibrosed gallbladder had essentially fused itself to the lateral edge of the duodenum creating a contiguous lumen, and the force of the retractor lifting the liver tore this area open, leaving me with a substantial duodenal defect to deal with. The only safe option seemed to be duodenal exclusion (staple across the pylorus and redirect food through a gastrojejunostomy downstream). The tissues of the involved duodenum were worthless; pale and scarified and non-pliable. The sutures I placed didn't hold. I ended up closing the defect with a serosal patch from proximal jejunum. It was all I could do. I left a couple of JP drains and got out of Dodge.

Three days later, the inevitable occured; bile started accumulating in the JP drains. Not unexpected, at least the duodenal fistula was controlled with the external drains. He stabilized initially but after about a week he developed shortness of breath and the source was identified as a large pleural effusion on the right side. Likely this was a reactive effusion that developed secondary to the duodenal leak, or maybe it would have developed anyway, regardless of whether I explored the gallbladder or not. He was old. It was emergency surgery. Who knows. That's what I sometimes tell myself at least.

The man ended up going for a CT guided drainage of the effusion. Six hours later he was dead, succumbing to a rare complication of the drainage procedure.

I think about that case a lot, though not as much as before. Enough time has elapsed. But I don't want to forget it entirely. Flashes of images/thoughts flood my consciousness. Driving in to the hospital at breakneck speed, too late, already pronounced dead. The phone call I made to the eldest son, informing him that his father, who seemed to be doing so well, was suddenly dead. Filling out the death certificate. "Complications following recent surgery". What if. Why did you have to go poking around at the gallbladder? Case could've been much shorter. Should have been? Tried to do too much. To be a hero? Overestimated knowledge/capabilities? Error in judgment. What have I done? The loss. The son who must bury his father on a rainy Thursday while I have a nice uneventful dinner with my family. And having to wake up and do it all over again the next day. Calling for scalpel. As if nothing happened. The unobtainable forced forgetfulness of a surgeon. Shake it off. Roll with those punches. Do it again. Only do it better this time. Lights on. Another patient waits, asleep and vulnerable. They trust you. Do the right thing. A fresh start. Knife please.....

But there's a balancing counterpoise to the thrill of heroism. The things we do as surgeons to our patients are saddled with the weight of potential complications. An ICU nurse I know always asks me if I've "committed any surgery on people today". She's kidding of course (at least she better be!), but her comment is tinged with an element of truth. It's an act of controlled violence, surgery, and the consequences of that act are unpredictable. We do the best we can. Any surgeon will tell you that. There's never intent to harm a patient but once that scalpel slaps into our palm, we knowingly take on the burden of ultimately realizing a suboptimal outcome, an outcome that is a direct consequence of the maneuvers we are about to perform. That's life as a surgeon. One out of every 450 gallbladders we do will result in a major bile duct complication. 8-10% of all colorectal anastomoses we perform will leak, to varying degrees of severity. Wound infections will plague 10-15% of our laparotomy incisions. One to five out of every 100 inguinal hernia repairs we do will fail. 3% of those patients who undergo a Whipple for pancreatic cancer won't walk out of the hospital alive. About 5% of patients undergoing thyroid surgery will sustain an injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, with 20% of these patients suffering permanent voice damage. It's a minefield of cold hard statistics we navigate through each and every day.

I suppose most doctors deal with it, this sense of guilt that develops when something goes wrong. But I doubt anyone bears a greater burden than the surgeon. The internist (assuming not a careless ass) knows deep down in her heart that she prescribed all the correct medications, listened to her patient's complaints, diagnosed everything correctly. She can take some solace in the fact the patient was not entirely compliant, or had a horrible family history of cardiac disease, or maybe just developed some ridiculously rare metabolic disease that any doctor would have struggled to diagnose. It's not so easy to rationalize when you've just operated on someone and they don't do well. The second guessing never stops, incessantly tormenting your sleepless nights, heart racing, pacing the darkened halls of your house, desperately trying to visualize from the depths of memory the moment in time during the operation when you cut this or sutured that, searching to no avail for that instant when you could have done something better, another stitch, a different technique, another instrument, a sign or symptom you missed, a less risky maneuver, something, anything that would have prevented the current state of affairs, your patient in the ICU, frightened, worse off for the moment than she was before the surgery. We all have these cases. Every surgeon has complications and bad outcomes. The ones that deny it are either liars or they don't operate nearly enough.

I remember a patient specifically from my early career. Three weeks after I started as an attending surgeon I was called on a Sunday to see an elderly guy with a bad bowel obstruction. His white count was elevated and the nurse mentioned he was having a lot of pain so I came in to see him. He certainly had an acute abdomen and, in reviewing the CT scan, he had all the pathognomonic findings of a rare entity known as gallstone ileus (pneumobilia, calcified mass in the terminal ileum). What happens is, a large stone from the gallbladder over time erodes into the duodenum creating a wide mouthed fistula between the biliary and intestinal tracts. The stone drops into the duodenum and migrates slowly downstream. Eventually it wedges itself into a spot in the bowel where it can't go any further, usually in the terminal ileum or ileocecal valve. The result is a high grade small bowel obstruction. The only solution is an operation. Classic surgical dogma teaches that your agenda during the operation is simply to alleviate the bowel obstruction. Take out the stone, do a limited small bowel resection, whatever is necessary. As for the gallbladder and any other potential stones, you were supposed to defer that battle for another day. When I was a chief resident, however, I had read some newer literature suggesting that, in the event the patient was stable and didn't have too many other co-morbidities, it would be reasonable to pursue the source of the pathology (cholecystectomy) during the same operation. So I fixed the bowel obstruction and we'd only been under anesthesia for about twenty minutes. I noted that the patient seemed stable. His vitals were rock solid. His past medical history was pretty unremarkable; no heart disease to speak of. So I rearranged my retractors and took a look up near the liver. Everything seemed somewhat scarred down and distorted. Seconds after placing the retractor to heft the edge of the liver up out of the way, my heart sank as a rush of green bile filled the operative field. What happened was that a very small, fibrosed gallbladder had essentially fused itself to the lateral edge of the duodenum creating a contiguous lumen, and the force of the retractor lifting the liver tore this area open, leaving me with a substantial duodenal defect to deal with. The only safe option seemed to be duodenal exclusion (staple across the pylorus and redirect food through a gastrojejunostomy downstream). The tissues of the involved duodenum were worthless; pale and scarified and non-pliable. The sutures I placed didn't hold. I ended up closing the defect with a serosal patch from proximal jejunum. It was all I could do. I left a couple of JP drains and got out of Dodge.

Three days later, the inevitable occured; bile started accumulating in the JP drains. Not unexpected, at least the duodenal fistula was controlled with the external drains. He stabilized initially but after about a week he developed shortness of breath and the source was identified as a large pleural effusion on the right side. Likely this was a reactive effusion that developed secondary to the duodenal leak, or maybe it would have developed anyway, regardless of whether I explored the gallbladder or not. He was old. It was emergency surgery. Who knows. That's what I sometimes tell myself at least.

The man ended up going for a CT guided drainage of the effusion. Six hours later he was dead, succumbing to a rare complication of the drainage procedure.

I think about that case a lot, though not as much as before. Enough time has elapsed. But I don't want to forget it entirely. Flashes of images/thoughts flood my consciousness. Driving in to the hospital at breakneck speed, too late, already pronounced dead. The phone call I made to the eldest son, informing him that his father, who seemed to be doing so well, was suddenly dead. Filling out the death certificate. "Complications following recent surgery". What if. Why did you have to go poking around at the gallbladder? Case could've been much shorter. Should have been? Tried to do too much. To be a hero? Overestimated knowledge/capabilities? Error in judgment. What have I done? The loss. The son who must bury his father on a rainy Thursday while I have a nice uneventful dinner with my family. And having to wake up and do it all over again the next day. Calling for scalpel. As if nothing happened. The unobtainable forced forgetfulness of a surgeon. Shake it off. Roll with those punches. Do it again. Only do it better this time. Lights on. Another patient waits, asleep and vulnerable. They trust you. Do the right thing. A fresh start. Knife please.....

Rushing

There's this old guy with dementia/chf etc who came in with SOB and a dislodged gastrostomy tube. He isn't one of those quiet/gorked-out type of demented guys either. You walk in his room and he starts rambling incessantly. "Doctor, let me ask you a question..." and then he trails off, mumbles or else "Doctor, dont leave, I have to know something...." whenever I try to leave, but he never completes a thought. He never actually asks me anything. It's annoying I'll admit. I don't usually spend a lot of time in his room. I just want to get in, get out, make sure the new tube is working properly and sign off the case as soon as I can. Well the last day I went in and his wife was there. She's this small, frail, soft-voiced old lady who sat quietly in the corner in the shadows when I was examining him. I didn't notice her at first. As I pulled up his covers and made to leave, he started his usual demented rambling. "Doctor I have to ask you.." And his little wife shot up out of the chair in a flash and was holding his hand saying Joe, Joe what is it you want to ask the doctor and his eyes looked scared and she said Im here Joe Im here Joe just tell me what you want to ask the doctor. And then he went silent. He just stared at her. He looked terrified and lost. And then she started crying I know Joe it's ok it's ok Joe and kept holding his hand and she looked at me and I felt like the biggest asshole for wanting to rush through things and sign off the case. I'm sorry I said, hoping she would understand everything I meant by that and I stood there and rubbed his damn shoulder or something like that for a while and then I left....

Saturday, November 7, 2009

Awesome

Jon Stewart with a dead-on Glenn Beck.

(h/t Little Green Footballs)

| The Daily Show With Jon Stewart | Mon - Thurs 11p / 10c | |||

| www.thedailyshow.com | ||||

| ||||

(h/t Little Green Footballs)

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

Annals of Wasted Resources

I performed an uneventful laparoscopic right colectomy on gentlemen a few weeks ago that went quite well. The following morning he was started on clear liquids and he was ambulated to the hallways. He looked great. His vitals were pristine. His abdominal exam was benign. He had excellent bowel sounds (I know, unreliable but I like hearing them nonetheless) and was even passing gas. His CBC, however, showed a WBC count of 15.7. Reactive white blood cell counts 18 hours after surgery are pretty much par for the course and they don't really bother us as long as the patient is doing well clinically.

When I saw him later that afternoon, he was tolerating his liquid diet and was making laps around the nursing station with his IV pole. But he asked me, "doc, why did I have to get all those needle sticks and tests today?" I had no idea what he was talking about. So I checked the chart.

The primary care doctor saw the WBC count that morning on rounds and was obviously much more concerned than I was. Eminently concerned. Freaked out would be another way of putting it. So this was what was ordered: blood cultures x 2, urinalysis and culture, CXR PA and lateral views, sputum cultures, an ID consult, and a CT of the abdomen and pelvis!!!!

I was able to get the CT scan cancelled but the rest of the orders were carried out as written. The ID consultant's note was two sentences. None of the cultures grew out anything. The CXR was negative. The patient went home two days later...

When I saw him later that afternoon, he was tolerating his liquid diet and was making laps around the nursing station with his IV pole. But he asked me, "doc, why did I have to get all those needle sticks and tests today?" I had no idea what he was talking about. So I checked the chart.

The primary care doctor saw the WBC count that morning on rounds and was obviously much more concerned than I was. Eminently concerned. Freaked out would be another way of putting it. So this was what was ordered: blood cultures x 2, urinalysis and culture, CXR PA and lateral views, sputum cultures, an ID consult, and a CT of the abdomen and pelvis!!!!

I was able to get the CT scan cancelled but the rest of the orders were carried out as written. The ID consultant's note was two sentences. None of the cultures grew out anything. The CXR was negative. The patient went home two days later...

That doesn't belong there...

This elderly (mid nineties) lady presented with nausea and profuse vomiting for a couple of days. An NG tube was placed and the above scan was obtained. What you're looking at is an incarcerated paraesophageal hernia complicated by a gastric volvulus. She was taken semi-emergently to the OR where the stomach was reduced from the thorax, the sac taken down, the hiatal crura reapproximated, and a gastropexy was performed. She actually recovered quite well...

Saturday, October 31, 2009

NFL Head Trauma

Malcolm Gladwell has an illuminating article in last week's New Yorker about an entity known as Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) which is a variant of cognitive dementia that develops in people who are subjected to repeated blows to the head (pugilists and football players especially). The article is debased slightly by the usual Gladwellian attempt to make a forced correlation between two seemingly unrelated topics (in this case dogfighting and NFL linemen), but it's a decent read nonetheless.

A recent study from Boston University delineates the pathophysiology of CTE as relating to abnormal deposition of the tau protein (whatever that is). Another study from the University of Michigan reports that former NFL football players develop early onset dementia or memory loss at a rate 19 times higher than the general male population between the ages of 30-49. There was even a sample from a teenage football player whose brain showed abnormal levels of the tau protein.

The bottom line is that football is an extremely dangerous activity. The dog fighter analogy is a stretch but these guys who play professional football for a living are indeed the gladiators of our age. Especially the interior linemen. And none of their contracts are guaranteed, that's the best part. These billionaire owners can cut a guy at any time, for any reason. Injury prone? Too many concussions? Out the door. So these guys play through it. They lace up their pads until they can't physically do it anymore. And too many of them are ending up like Mike Webster after their playing days have ended, sleeping under highway bypasses with all the other bums....

Friday, October 30, 2009

Cool Tune for the Weekend

Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeroes. If you're feeling the least bit broken down, sad-souled, cornered and depressed...this tune will make you happy.

Thursday, October 29, 2009

The Doctor Fix

I haven't read much in the med blogosphere about the so-called doctor fix. Last week, word leaked out that a version of the Democratic health care plan included a provision that would eliminate planned Medicare cuts to physicians as mandated by a 1997 federal law. This law used a complex formula, known as the sustainable growth rate (SGR), to limit federal spending on health care. The idea was to prevent spending on health care from growing faster than the economy. The problem is that spiralling health care costs have in fact grown exponentially faster than the economy. Therefore, as demanded by the SGR formula, doctors should have seen reimbursement cuts of 20-40% over the past few years. Given the tight balance between profitability and bankruptcy that most primary care docs negotiate, such drastic cuts would lead to a near collapse of private practice as a business model. So every year, Congress passes a one time bill that defers those cuts until the next fiscal year. In the most recent iteration of Obamacare 2009, the plan was to completely do away with any future Medicare cuts for the next ten years by subsidizing the cuts with $240 billion of federal money. The problem is that this subsidy was completely unfunded (sort of like GW Bush's prescription benefit bill) and more moderate congressmen went nuts. The idea is now dead in the water.

The whole thing is amusing to me in this respect. Remember when J. James Rohack (President of the AMA) wrote a guest post on Kevin MD enthusiastically supporting Obamacare back in August, mainly because of promises to do away with any future SGR cuts? I can't wait to read his follow up piece. Tort reform gets taken off the table early in the game and our AMA President is ok with it. Because, you see, our noble politicians in Washington promised him that the SGR issue would be "fixed". And this bad faith effort to effect reform by slapping together an absurd plan to simply write off the SGR cuts as unfunded debt for ten years represents an ingenius form of cynicism, even for our wily DC politicos. Of course the plan was going to get panned. Of course public backlash would make passage of the bill impossible. So it's out. And now we're back to square one. Obamacare has moved on, closer than ever to becoming a reality. And it still carries an endorsement from the AMA, even though the giant carrot that warranted that endorsement has been disregarded....

UPDATE:

The WSJ Health Blog reports that the doctor fix is still in play, unfunded as before. Only now it's going to be implemented via a separate bill. That way there, Obamacare isn't contaminated by the stigma of having anything in it that will increase the federal debt. I hope Dr Rohack is pleased...

The whole thing is amusing to me in this respect. Remember when J. James Rohack (President of the AMA) wrote a guest post on Kevin MD enthusiastically supporting Obamacare back in August, mainly because of promises to do away with any future SGR cuts? I can't wait to read his follow up piece. Tort reform gets taken off the table early in the game and our AMA President is ok with it. Because, you see, our noble politicians in Washington promised him that the SGR issue would be "fixed". And this bad faith effort to effect reform by slapping together an absurd plan to simply write off the SGR cuts as unfunded debt for ten years represents an ingenius form of cynicism, even for our wily DC politicos. Of course the plan was going to get panned. Of course public backlash would make passage of the bill impossible. So it's out. And now we're back to square one. Obamacare has moved on, closer than ever to becoming a reality. And it still carries an endorsement from the AMA, even though the giant carrot that warranted that endorsement has been disregarded....

UPDATE:

The WSJ Health Blog reports that the doctor fix is still in play, unfunded as before. Only now it's going to be implemented via a separate bill. That way there, Obamacare isn't contaminated by the stigma of having anything in it that will increase the federal debt. I hope Dr Rohack is pleased...

Mammology

A NY Times op ed from October 10 makes the case that the management of breast cancer ought to be coordinated and run entirely by fellowship trained specialists hereafter to be known as "mammologists". The article was written by an OB/Gyn who runs the breast fellowship program at the University of Rich Rod. Basically, it's another barely camouflaged attempt by a sub-sub specialist to corner the surgical market on a type of operation that is about as straight forward and simple as it gets. (Surgical training programs assign junior residents and interns to all the breast lumpectomies). The decision-making in breast oncology is certainly complex and patients benefit from a multi-disciplinarian approach but the actual surgical procedures are not exactly enigmatic. The idea that you need to have your mastectomy done by an expert, i.e. a "breast surgeon" is rather absurd.

But the article does raise an interesting point. Specifically, why don't OB/Gynes do breast surgery? They do pap smears and pelvic exams and formal breast exams and usually are the ones who order yearly mammograms on their patients. It has always struck me as odd that once breast pathology is identified, the patient is all of a sudden shunted off to a general surgeon.

The super-specialization of surgery is an apparent inevitability. The paradigm of practicing "general surgery" is a dying ideal. I can read the writing on the wall. But these specialists are going to have to do a better job in coming up with new appellations. I mean, "mammologist"? That sounds terrible. It sounds zoologic. Just call yourself a breast surgeon, dammit.

Blog Break

Yeah I know, I haven't been around. It's been a combination of being incredibly busy at work and stressed out and hitting the wall a bit creatively. It happens. Blogging is a demanding endeavor. Don't let anyone tell you anything differently, especially with the format I do (original posts, not much linking). You reach a point throughout the year where you just sort of get sick of hearing yourself opine on various topics. Blogging is intrinsically a narcissistic, self-indulgent hobby; presenting YOUR TAKE on the latest medical controversy for all the world to hear, constantly positioning yourself on various issues, proclaiming your own special stance in an open forum. It's exhausting. But whatever. Blog posts that talk about how tiresome and tough blogging can be are annoying. So I'll stop. I'll start posting again. I have a few things in mind...

I have been doing some reading at night. Check out these recs:

-Robert Wright's Evolution of God

-Anything from Richard Hofstadter (especially Anti-Intellectualism in American Life)

-James McPherson's one volume Civil War history Battle Cry of Freedom

I have been doing some reading at night. Check out these recs:

-Robert Wright's Evolution of God

-Anything from Richard Hofstadter (especially Anti-Intellectualism in American Life)

-James McPherson's one volume Civil War history Battle Cry of Freedom

Thursday, October 15, 2009

Front row seats

This survey paper from Archives of Surgery in August addresses public/health professional viewpoints on end of life interventions, specifically in situations of severe traumatic injuries ultimately resulting in death. It isn't much of a paper. Surveys are bogus. I think there was only a 50% response rate. But whatever. Here's what I want to highlight:

General impressions can be gleaned, which are often just as useful as meticulously parameterized data. And the general impression of this paper---that both the lay public and health care professionals would prefer to be in a trauma bay during the resuscitation of an traumatically injured child---- is just outlandish to me.

On trauma call one day as a 4th year resident, they rolled in a four year old kid from Chicago's south side who had run out into the street and got drilled by a speeding car (hit and run). He lost his vitals the minute he arrived. He was blond and blue eyed and there was dirt under his fingernails and we were pumping his pale, frail chest and finally the Trauma attending performed an ED thoracotomy. His tiny little pink lung erupted through the wound and his heart fluttered uselessly in its pristine diaphanous sac. There was no blood in the chest. He clamped the aorta and massaged the heart directly. Still no vitals. The next maneuver was a debatable one, in retrospect, but it was almost as if he, all of us in the room collectively, felt the need to do something else, to keep working, anything to avoid stopping, admitting futility. The child's belly had seemed to distend during the resuscitation. So the attending opened up his virgin abdomen, hoping to encounter hemoperitoneum, possibly to clamp the supraceliac aorta, possibly to find a specific injury to repair or at least temporize. There was nothing. The translucent, parchment-thin bowels bulged through the incision. There was no blood. His little liver was beautiful, I remember thinking. Nothing to fix. The vitals never came back and the kid died right there in front of us all with lung and loops of intestines spilled out everywhere. The attending closed the wounds himself, alone, the curtain pulled shut...

I think I put three holes in the call room wall right afterwards. How can something like that happen? For what reason? I still carry the kid's newspaper obituary in my wallet, yellowed and deeply creased after all these years. I take it out every so often. It still pisses me off to this day. I don't want to ever see something like that again...

Most of the public (51.9%) and the professionals (62.7%) would prefer to be present in the treatment room as opposed to the waiting room in the ED during resuscitation of a loved one (Table 2). This preference endured even when respondents may witness disturbing sights. If the victim were a child, the preference for being in the treatment room increased to 79.0% of the public and 78.7% of the professionals.

General impressions can be gleaned, which are often just as useful as meticulously parameterized data. And the general impression of this paper---that both the lay public and health care professionals would prefer to be in a trauma bay during the resuscitation of an traumatically injured child---- is just outlandish to me.

On trauma call one day as a 4th year resident, they rolled in a four year old kid from Chicago's south side who had run out into the street and got drilled by a speeding car (hit and run). He lost his vitals the minute he arrived. He was blond and blue eyed and there was dirt under his fingernails and we were pumping his pale, frail chest and finally the Trauma attending performed an ED thoracotomy. His tiny little pink lung erupted through the wound and his heart fluttered uselessly in its pristine diaphanous sac. There was no blood in the chest. He clamped the aorta and massaged the heart directly. Still no vitals. The next maneuver was a debatable one, in retrospect, but it was almost as if he, all of us in the room collectively, felt the need to do something else, to keep working, anything to avoid stopping, admitting futility. The child's belly had seemed to distend during the resuscitation. So the attending opened up his virgin abdomen, hoping to encounter hemoperitoneum, possibly to clamp the supraceliac aorta, possibly to find a specific injury to repair or at least temporize. There was nothing. The translucent, parchment-thin bowels bulged through the incision. There was no blood. His little liver was beautiful, I remember thinking. Nothing to fix. The vitals never came back and the kid died right there in front of us all with lung and loops of intestines spilled out everywhere. The attending closed the wounds himself, alone, the curtain pulled shut...

I think I put three holes in the call room wall right afterwards. How can something like that happen? For what reason? I still carry the kid's newspaper obituary in my wallet, yellowed and deeply creased after all these years. I take it out every so often. It still pisses me off to this day. I don't want to ever see something like that again...

Wednesday, October 14, 2009

Executions on Hold

Ted Strickland has placed a halt on any further executions in the state of Ohio pending a full review of the state's lethal injection process. As you may recall, I wrote about the botched execution of convicted murderer Romell Broom last month. Broom has terrible veins and no one was able to establish IV access for the administration of the lethal drug cocktail. After jabbing him for 2 hours, the execution was aborted. For now, all further executions are on hold until the state clarifies how it will handle future access problems.

What the hell is the plan? Is there an ongoing search for an ace IV access professional right now? Are there ads on Craigslist and Monster.com and MDSearch.com?

"Seeking professional vascular access practitioner, qualified and adept in the art of placing temporary vascular access catheters. Must be comfortable performing for a live audience who watch from behind bullet proof glass. Past experience in palliative care and end-of-life management helpful. Leather executioner's hood provided free of charge. Hippocratic oath optional. Would be a government employee. Full benefits included in salary."

What the hell is the plan? Is there an ongoing search for an ace IV access professional right now? Are there ads on Craigslist and Monster.com and MDSearch.com?

"Seeking professional vascular access practitioner, qualified and adept in the art of placing temporary vascular access catheters. Must be comfortable performing for a live audience who watch from behind bullet proof glass. Past experience in palliative care and end-of-life management helpful. Leather executioner's hood provided free of charge. Hippocratic oath optional. Would be a government employee. Full benefits included in salary."

Monday, October 12, 2009

Clostridial Difficile Colitis

Since becoming an Attending Surgeon, I've performed 17 subtotal colectomies (went back and counted) on patients with fulminant c diff colitis over the past three years. As a resident, I don't recall ever doing or even hearing of a patient getting a colectomy for severe c diff. But it's a growing trend. This is a disease entity that didn't exist 15 years ago. Antibiotic induced alteration of colonic bacterial flora allows for overgrowth of this normally non-pathogenic bug. The spectrum of severity is broad, with rare cases (1-5%) progressing to the severe variety of fulminant colitis. What we're finding is that earlier surgical intervention in these severe cases represents the patient's best chance at survival.

There's a good review of fulminant c diff colitis in the May 2009 Archives issue from Harvard. Fulminant colitis is defined by the presence of systemic toxicity. Some salient points:

*In-hospital mortality was 35%

*Three key indicators of mortality were WBC >35k/bandemia, age >70, cardiopulmonary failure/need for pressors/vent

*Earlier surgery was associated with improved survival

The most interesting point was that patient outcomes correlated with which service (surgical vs medicine) that the patient was admitted to. Patients on a surgical service were 3 times more likely to survive fulminant colitis than those patients cared for by the medicine service. They were operated on more frequently and more expeditiously (as one would assume).

So the question is: If fulminant c diff colitis is a surgical disease, shouldn't all patients immediately be transferred to a surgical service once signs of systemic toxicity set in? If the patient is "sick" (renal failure, hypotensive, septic, etc) and has peritonitis on exam, I proceed directly to the OR. Some of these patients I fear are lingering on the medical service with a diagnosis of "infectious colitis" for far too long. Not all c diff is a surgical problem, just like not all cases of acute pancreatitis need to be followed by a surgeon. But it's important to properly stratify these patients and get the surgeon involved sooner rather than later...

Saturday, October 10, 2009

Weekend Picture

That's a child harmed by an American airstrike in Afghanistan. It's not clear whether this was an unmanned Predator drone that strafed the boy's village. Congratulations to President Obama on the Nobel Peace Prize. Hopefully, the honor will inspire him to embark on a rational strategy that seeks to de-emphasize the "perpetual war state" policy that currently defines our country's foreign affairs. Korea, Vietnam, the proxy wars of Central America in the 80's, Desert Storm, Iraq, and now the interminable 8 year-long Afghanistan misadventure. Isn't it time we lay down our guns for a few years and start to address the serious problems within our borders (health care, post-industrial employment, economic collapse) that threaten us exponentially more than a bunch of Islamic sheep herders and opium lords half way around the world? Just a thought.

CBO Changes its Mind on MedMal Reform

CBO Director Doug Elmendorf, never one to acquiese to political pressures, is now stating that medical malpractice reform will lead to over $50 billion in savings over the next ten years. This new claim is based entirely on the premise that defensive medicine has heretofore been underestimated as a source of skyrocketing health care costs. (Previously, atempts to quantify med mal reform were limited to effects on liability insurance premiums). He hints that punitive damages caps ($250,000-$500,000) are a necessary adjunct to any serious attempt at reform.

Now I'm not married to the idea of capping damages. But there's no doubt that physicians in America are driven by fear of potential litigation. It's nice to finally see the federal government acknowledge this reality with objective data...

Now I'm not married to the idea of capping damages. But there's no doubt that physicians in America are driven by fear of potential litigation. It's nice to finally see the federal government acknowledge this reality with objective data...

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

In Defense of Scut

No specialty has been more affected (compromised?) by the notion of work hour reform than general surgery. With the introduction of the 80 hour work week, surgical interns and junior residents saw their hospital contact time cut drastically with deleterious consequences in terms of case load and relative comfort level taking care of typical surgical complications. Other data suggests that errors are paradoxically increased when surgical residents are forced to go home early post call because of continuity of care issues during patient hand offs.

I know I sound like a crotchety old timer, longing for the days of stumbling into my tiny studio apartment in Chicago as an intern with the AC broken, mindlessly whipping up a pan of Kraft mac and cheese, eating directly from pan, and crashing out on the couch with the half eaten mac/cheese on the floor and the TV on and the alarm set to go off at 4:00Am the next morning. Such fond memories indeed. But that sort of regimen made me an anal, relentless, rarely satisfied, tireless surgeon (at least when it comes to patient care). And everyone went through the same thing. So we held each other accountable. It became a way of life (goodbye golf, having beers till 2Am on a random Wednesday in Lincoln Park). And I don't regret it for a minute. I was brainwashed and indoctrinated, most definitely. But I wouldn't be the surgeon I am today without the experience of old school residency. You just can't make up for the lost face time and hours and hours of hours of unfiltered hospital life. There are no books you can read at home to reproduce it. No Youtube videos to watch. No "intensive resident education seminars" that will replace the value of simply spending an ungodly amount of time in the hospital.

One of the arguments for work hour reform is this idea that residents spend too much time doing scut. Scut is the bane of the intern's existence. Go draw a CBC on patient X. Go wheel Mr Y down to cardiology for his stat echocardiogram. Go down to radiology and get hard copies of Mrs M's MRI. Write transfer orders on 6 patients in the ICU. Call the outside hospital to get records of patient G faxed to us by noon. When the senior residents would alight their gaze upon you with that look of "Man, I hate to have to ask you this but..." it's just soul crushing. But you did it. The whole time you're grumbling to yourself about how such mindless toil is beneath you and unworthy of the efforts of someone so highly educated. Is this why I studied so hard all these years?